“Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.” –

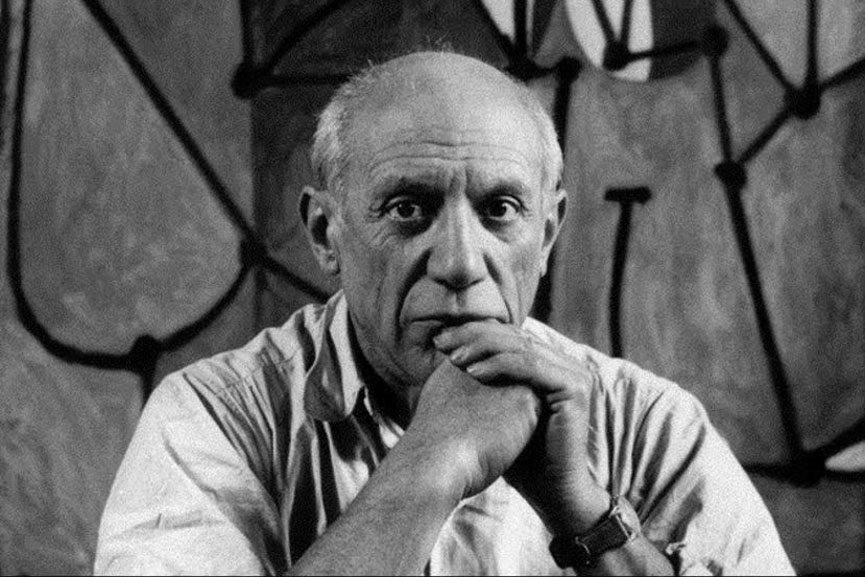

Pablo Picasso

“Before Picasso could dabble in Cubism, he had to become a master of basic drawing.” –

Blake Snyder, Save the Cat!®

For generations of creatives, Pablo Picasso has embodied the artist’s unfettered spirit. In his work they see the direct expression of his most visceral emotions and deeply held beliefs. He was the avatar of the true artist, heroically refusing to let the conventions of the day filter and dim the presentation of his vision.

“Conventions.” “Structure.” “Paradigms.” Young artists—painters, writers, musicians—hear those words and picture the straps on a straitjacket. “Yes, thank you for all your ‘rules’ but what about my passion? What about my art? What about Picasso?”

In fact, the art world’s most famous revolutionary started studying the rules when he was seven years old. Picasso’s father was himself an artist who trained Pablo in the basics of figure drawing and oil painting. Picasso’s biographer describes his father as “a traditional, academic artist and instructor who believed that proper training required disciplined copying of the masters.”

“He was a strict disciplinarian, obeying the law to the letter and requiring both obedience and hard work; it was a rigorously academic training.”

And how did the pupil respond? The biographer reports that Picasso accepted the discipline happily and thrived on his father’s numerous assignments.

“What for most people is a hopelessly arid exercise is a delight to Picasso, and his art-school studies glow with pleasure: controlled, disciplined, and almost anonymous, but certainly pleasure.”

In 1895 Picasso enrolled at Barcelona’s La Lonja School of Fine Arts after his father obtained a position there. A year later he painted The First Communion.

In it, Picasso employs techniques of composition, perspective, and shading that Velázquez might have used two centuries earlier. And he could not have chosen a subject with greater mainstream appeal. In a deeply religious and conservative country, the story of a girl’s first communion would find the widest possible audience. Had Picasso pitched his idea for the painting to a studio, there would have been talk of great family films and a Christmas release date.

Look at The First Communion, then consider some of Picasso’s later masterpieces. It’s hard to believe that the same person produced them all. Like any great artist, Picasso’s work evolved over time. But clearly, his realistic portrayal of a young girl kneeling at an altar did not compromise his ability to depict the Barcelona prostitutes featured in the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

And his celebration of a conventional, establishment ritual in no way weakened his attack against that same establishment in Guernica.

By thoroughly understanding traditional modes of expression, he was better able to devise new ones which could more effectively present his vision. Over time, he traded the standard artist’s palette for one filled with only shades of blue. His vision evolved and a Rose Period followed the Blue Period. In Guernica color disappears entirely and we see a hellscape presented in black, white, and gray.

Work your way backward through Picasso’s catalogue and think of it as an archaeologist’s dig. At the bottom you find a solid foundation upon which he built his remarkable body of work.

So if you are an aspiring artist and you find yourself raging against the rules, consider Picasso. Then ask yourself whether beneath your anger is also a bit of fear. Fear that something you care dearly about will be compromised, that a message the world needs to hear will be muted. And more: fear that if you don’t master a particular rule book, you will never realize your dream of becoming an artist.

It takes great courage to commit to the creative life, but this is one concern you can set aside.

Think of time-tested approaches—whether they are Aristotle’s Poetics or Blake Snyder’s beats—as items in a toolbox. Master them: you may be surprised at how well they suit your needs. If you discover that you need more tools, go out and find them. People have been developing them for thousands of years.

And if after all that you still haven’t found the tool you need, invent a new one. Then be sure to share it—your fellow artists will thank you for the help.

Rich Kaplan

5 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rich, this makes so much sense to me. Picasso’s training led him to great works, however different & extraordinary from his first painting. My editor basically said the same about my first book just finished. Now that I’ve learned the basic, it’s time to write another—apply and expand on what you learned. And I’m writing a sequel. Querying agents now and planning the sequel. Onward with passion & persistence. ?? Christine

Thanks, Christine. Best of luck with the sequel.

Rich- what you did here… is as mesmerizing to me as seeing “The First Communion” for the first time. I love learning about Picasso early training under his father and appreciate how knowing the rules allowed him to later break them. It is inspiring way to tell Cat! nation to reflect on STC! beats to their craft and add to their tool box in order to write something amazing. Like Blake always said- ” A well written screenplay will sell itself!” And this blog post is so inspiring. God Bless!! – from a proud member Cat! Nation- Austin Cats!

Thanks, Melody – great to hear from you.

Would his modern works been considered art, if he had painted them as a young boy? No. To survive one must mimic the accepted behaviour of the herd mind to be considered non-threatening. Then once trusted and if one is brave enough to publicly challenge mainstream beliefs and the status quo, one might survive long enough to be able to be held high as an artist or die and their works be discovered at a later date. Did Picasso need the skills he learnt to paint modern art – No. But he did need to know them to break them – Yes. And, he did need the herd to approve of him and his works to be consideredan ‘artist’.