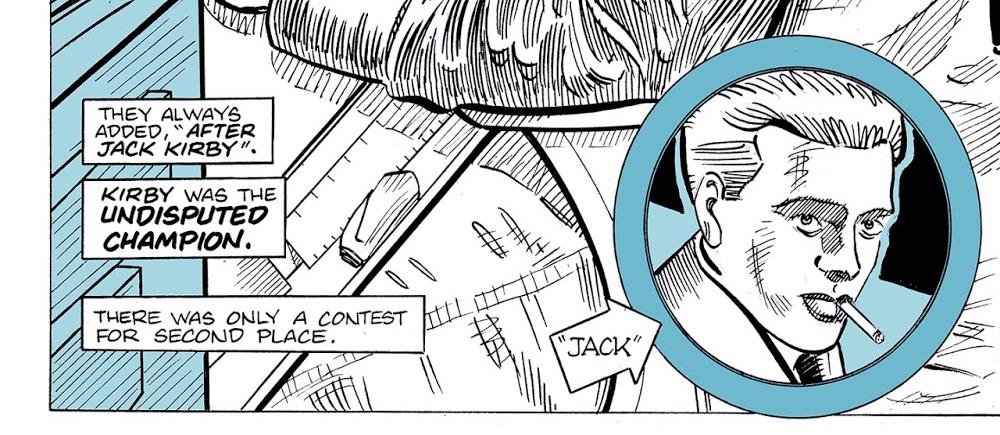

The term graphic novel is a fairly recent addition to the lexicon. Before that they were just called comic books. They were meant for kids and could be had at a corner store for 12 cents. The best ones like Uncle Scrooge, Little Lulu, Weird Fantasy, the Spirit, the Fantastic Four, and Spider-Man could be enjoyed by a universal audience. Most people stopped reading comics when they were 11 or 12 but I never stopped. I even went to art school to learn how to emulate the brilliant men who conveyed these fantasies.

I first got published as an amateur artist at age 16, in the fanzine “Comic and Crypt.” Soon, while teaching, I was getting paid to letter other people’s comics. Over time I worked as a colorist, editor, writer, inker, and penciller. I often wrote and drew very short stories–usually four to six pages. They could be drawn in my spare time and if something went wrong, be easily abandoned. After a while I jumped up to a 34 pager, then a 41 pager. Those were significant time commitments for a man with a day-job and a family.

But the market changed. It became easier to find a publisher for a long story than a short story. People weren’t buying anthologies. Stores wouldn’t stock them.

But the market changed. It became easier to find a publisher for a long story than a short story. People weren’t buying anthologies. Stores wouldn’t stock them.

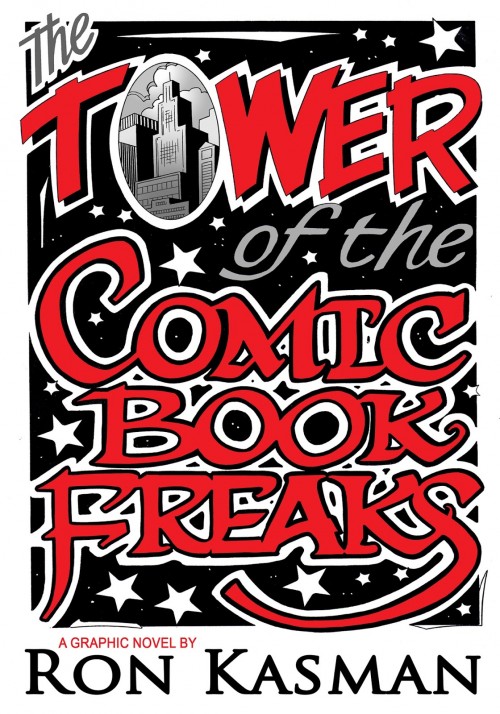

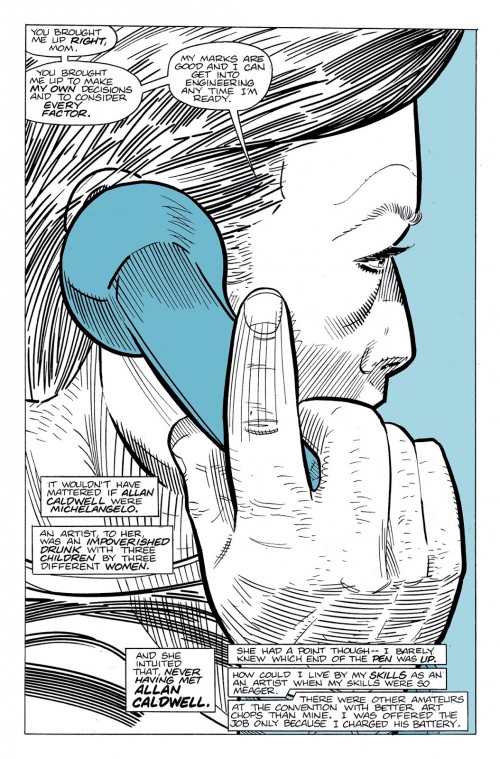

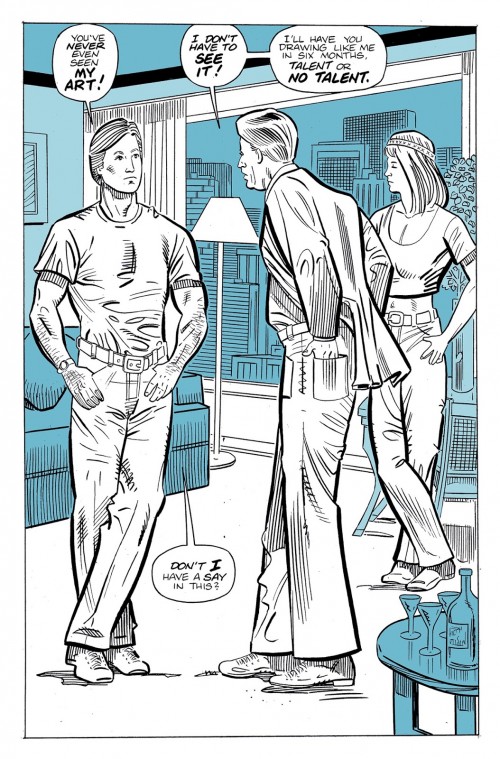

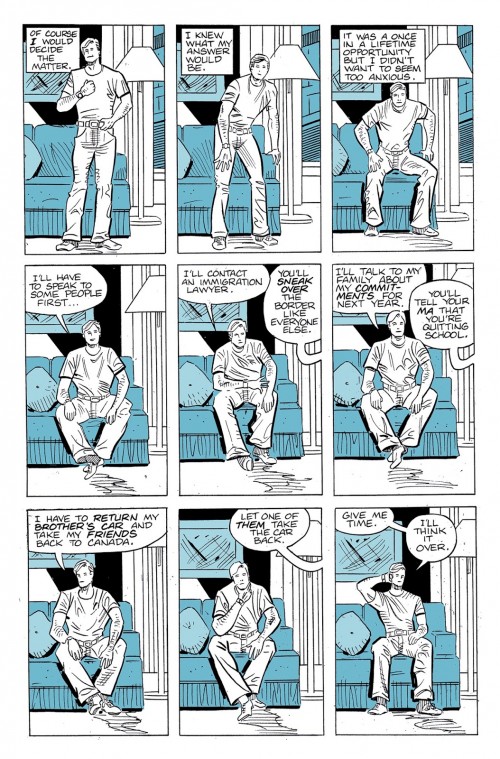

So, I roughed out five story ideas that would be appropriate for graphic novels. I didn’t go with the most commercial one, but one with commercial possibilities that would be fun to draw. The story is about five awkward young men who go to New York in 1971, when the city was in a state of extreme social decay. They attend an early comic convention looking for love, sex, work, art, and a look at the city’s wicked underbelly. My graphic novel, The Tower of the Comic Book Freaks, came in at 216 pages and took almost two years from start to finish. Some of my storytelling knowledge is from years of reflecting upon books, movies, TV, and comics. A crucial part is from reading books on how to write. I read Stephen King’s On Writing, Ben Bova’s The Craft of Writing Science Fiction That Sells, and Story by Robert McKee. I even read the DC book on how to write comics and all the other DC How-To Guides.

Some of my storytelling knowledge is from years of reflecting upon books, movies, TV, and comics. A crucial part is from reading books on how to write. I read Stephen King’s On Writing, Ben Bova’s The Craft of Writing Science Fiction That Sells, and Story by Robert McKee. I even read the DC book on how to write comics and all the other DC How-To Guides.

By far, the best book I read was Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder. When I tell people about it, I also tell them to go home and order it on Amazon… now.

A few weeks ago I wrote Blake Snyder a fan letter, just to tell him how important his book was in my process. I had no idea that he had left us. Save the Cat! is written so warmly, it is like listening to a friend talk. I was genuinely sad to hear of the death of this man whom I have never met. But all he created lives on.

Before reading Save the Cat!, I had little clue as to how to structure my stories. When doing a six pager, a comic book author can get away with most anything and still have an interesting story. At 20 pages, the length of most Marvel and DC stories, structure is still fairly easy to analyze. But how do you break down a 200-page story? Most of my method for creating structure was instinctual before I read Save the Cat! Because of Save the Cat!, a frequent comment I get is that my graphic novel is a page turner.

I did not call the breaks in the script Chapter One, Chapter Two, etc. By the second draft they became Opening Image, Theme Stated, Set-Up, Catalyst, and you will know the others if you have read Blake Snyder’s book. And I will accept his subtitle, “The Last Book on Screenwriting That You’ll Ever Need,” while finding irony in the fact that he wrote two more.

By the way, I did not accept everything he said. Mr. Snyder points out that his book shows how to write big box office style movies, not a film like Magnolia. I get it. I wanted a bit of an esoteric feel in there so I deviated, but never by much. My story remains built on his skeleton.

Here are some of the things I tried when writing The Tower of the Comic Book Freaks:

Here are some of the things I tried when writing The Tower of the Comic Book Freaks:

1. I wrote about something I cared about, hoping my delight in the subject would be contagious.

2. I picked something that I thought could gain a broad audience. I stress the word “could.”

3. I tried to make every panel interesting.

4. I had a hero with many good qualities but also some bad ones.

5. I created a unlikable villain who had reason to act the way he did.

6. I gave the protagonist distinctive friends.

7. I created a subplot involving love.

8. I gave the reader some unfamiliar information.

9. I gave the story a Hollywood ending.

10. I tried to minimize the captions but I consciously used captions, thought balloons, word balloons, and sound effects. They make comics unique.

11. I had exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement. At least I think I did.

12. I stayed away from emulating comic books, television, and SciFi. Those two media and that one genre are often repetitive and dull. Some of their creators, though, are so talented and flamboyant that they can make their tales interesting even while being a lot like everything else around. I am not quite so talented.

Some of my points are from Save the Cat!, most notably point #7. But by this time, they have become part of my writing style and I am really not sure where they originated.

My blog post here is being read by men and women who love the cinema. I do too. And it is easy to see that comics and film have always overlapped, now more than ever before. A few of my friends in comics have tried writing with film in mind, and one, Kaja Blackley, succeeded. His comic book, Dark Town, was made into the movie, Monkeybone. I have to hand it to Kaja.

Right now, on my street alone, there are four people that I know of writing screenplays. Think of the odds. I was told that there are about 250 Hollywood films made per year and that 90% of them are written by people who have written one previously. Steven Spielberg, I am not sitting next to the phone awaiting your call.

Here is what has happened with my book:

I laid out the graphic novel and knew that it would weigh in at 216 pages. When I finished page 89, I started sending packages out to publishers. I was rejected by the first sixteen. The most common rejection was simply no response. The second most common was that it did not fit into their publishing schedule. Yeah… but two of them let me know that I was on to something. I got long emails saying how wonderful the book was but that they wanted to make money and they wouldn’t do so on my book. One explained that the consumers buy the comics with Poison Ivy and Harley Quinn and if they have money left after purchasing those titles, they probably would buy X-Men or Spider-Man, not what I had to offer. I was being assured that the story was good, just not as commercial as the publishers wanted. I kept trying.

Submission seventeen was to Caliber Entertainment in Detroit, the good people who published The Crow, which later became the 10th biggest box office film in the year 2000. They have been in business 25 years. I have never heard a bad word about them. I got an email back the same day I submitted saying, “We’ll go with it. I’ll send a contract in about three days.” The note was from the president of the company, Mr. Gary Reed.

I was not altogether happy with the contract. I showed it to two friends, one a lawyer, one a long time comic artist. Independently, they said the same thing: “You have just been rejected by 16 companies. Sign the contract.” Later a third friend told me, “You might not like it but the terms are fairly standard for the industry. You wouldn’t have done better elsewhere.” I signed, telling the company that I needed another year to complete the book. I got it in 11 months later. They were happy.

Well, in getting published, I bought a ticket in an intellectual lottery. I could be the next Kaja Blackley, but it would take a bit of luck and a lot of perseverance. I think my book should be selling like Maus or Fun Home. But a lot of people have good graphic novels out and they can’t all be best sellers.

It got up to number 16 in its Amazon category, which includes thousands of books. It is sold in comic book stores and one store I know of sold 40 copies. I became a guest at conventions and bookstores. I have been reviewed in a half dozen newspapers. The book is in library systems across Canada. Parts of it are being exhibited in a museum. I am on podcasts. There are internet reviews aplenty. It has been enjoyed and recommended by accomplished professionals. And I got nominated for the Joe Shuster Award, a national award (here in Canada) as Best Cartoonist, for my work as the artist and writer on the book. Nine people were nominated. I lost to Jeff Lemire.

Though I realize it is unlikely, I actually do hope for a call from Steven Spielberg. But while I am waiting I am working on a second book, again using the lessons from Save the Cat! as the framework.

——————————————————————————————

If you want to see about 70 pages from The Tower of the Comic Book Freaks, go here.

If you want to see the first 30 pages or so, or just drop me a line I am at: [email protected]

And, if you want to buy a copy, check out its Amazon page.