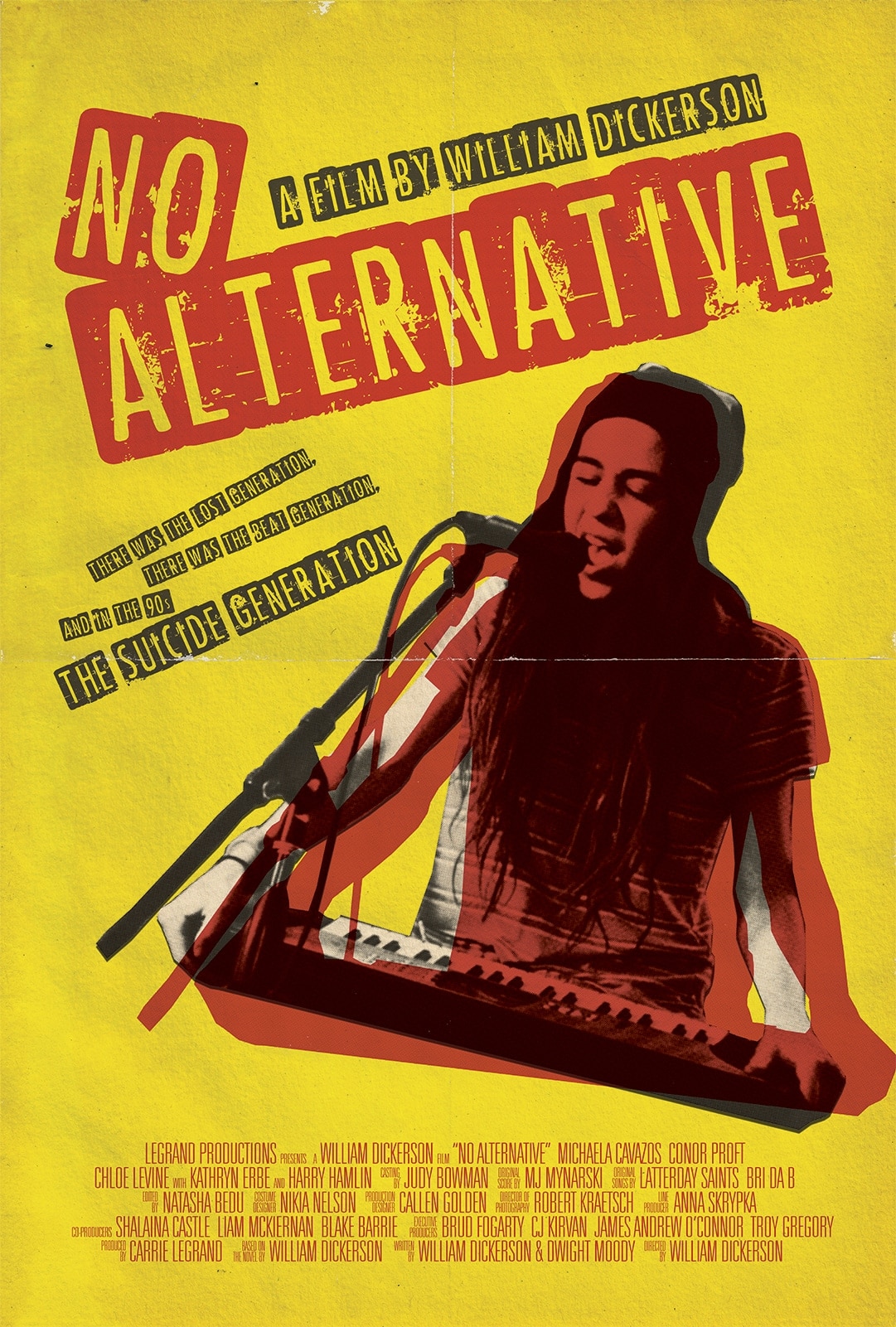

I’ve been working on No Alternative for over 12 years. I adapted the script for the recently released movie from a novel I wrote in 2012, a novel that was, in fact, adapted from my original screenplay.

I’ve been working on No Alternative for over 12 years. I adapted the script for the recently released movie from a novel I wrote in 2012, a novel that was, in fact, adapted from my original screenplay.

No Alternative started out as a script, but as often happens with a lot of screenplays, the project stalled. Just out of film school, attempting to make a period piece set in the ‘90s with an enormous cast and a slew of locations was an elaborate endeavor that proved to be impossible at the time.

While No Alternative was always meant to be an independent film, I figured it couldn’t hurt to have pre-existing material out there in the world, so while making my microbudget first feature, Detour, I copy-and-pasted the original script of No Alternative into a Microsoft Word document and started to type some meat onto that skeleton of slug lines, action paragraphs, and blocks of dialogue.

It took me a combined five years of script and novel writing to complete the book, which I published in 2012. While it’s difficult, of course, to write and publish a novel, it is logistically—and statistically—much easier to accomplish than to write, produce, and direct a movie. In fact, writing the novel was the most important thing I could have done to prepare me for rewriting the script.

From 2012 to 2015, I used the novel as a roadmap to refine the script. It allowed me to analyze the original screenplay, to become objective about the process, to be brutal in my self-criticism, to take it apart and put it all back together in better shape than it ever was.

Both the original script and the novel are structured in the same fashion—the story plays out in a chronological three act-structure, using the BS2 [the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet] as its outline—with one notable exception: the shift in point of view.

The script is written as a dual point of view, intercutting throughout the story between the brother, Thomas Harrison, and his sister, Bridget; however, the novel takes a third person omniscient point of view throughout, bouncing back and forth between the various characters, until the last act, when it switches to the first person point of view of one of the main characters who dies shortly before the act begins. This same character dies at the same point in the screenplay; however, the point of view shifts to the foil of the dead character—it could not be a more opposite approach.

In the novel, I was able to dive into the perspective of someone from beyond-the-grave, mining and excavating the thoughts the dead would have about the survivors. In the script, I was exploring the survivor’s thoughts on the dead.

In the novel, I was able to dive into the perspective of someone from beyond-the-grave, mining and excavating the thoughts the dead would have about the survivors. In the script, I was exploring the survivor’s thoughts on the dead.

While characters must be proactive in both mediums in order for a reader and viewer to root for them, in my experience, character proactivity in novel form offers tremendous power—the subjectivity of literally entering the thoughts and feelings of a character on a whim is, in many ways, unparalleled.

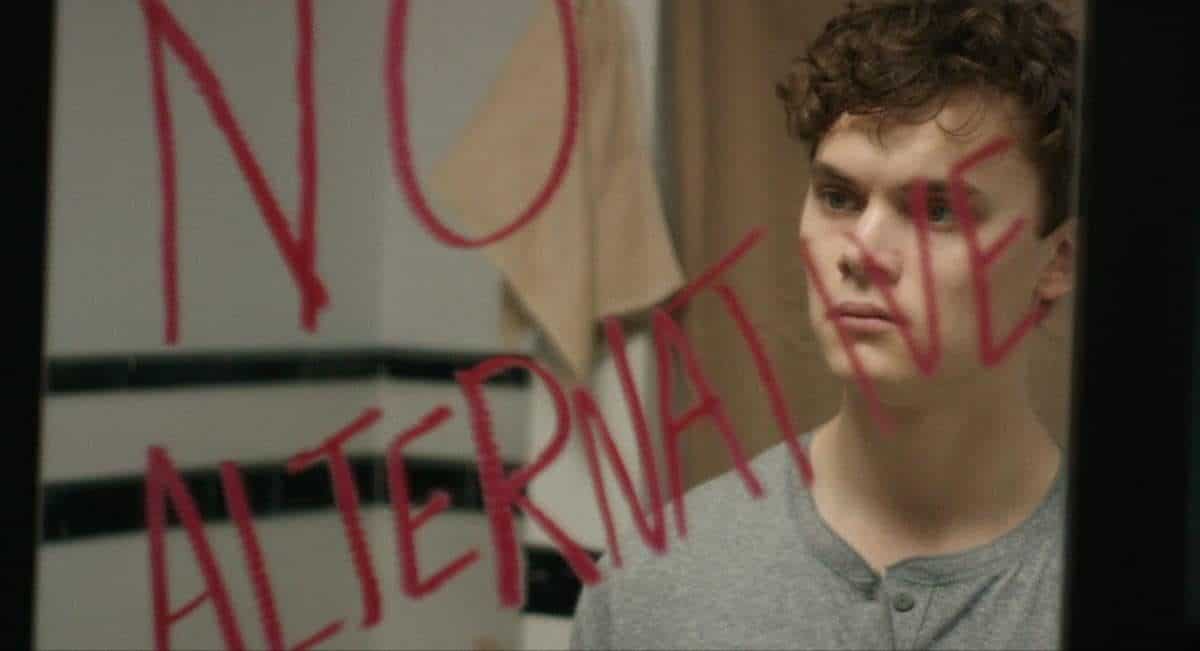

However, the reactions a character has on screen to monumental events in the character’s life also carries tremendous power: for example, an extreme close-up on the actor’s eyes as he witnesses something that changes him forever. The camera lens allows the viewer to experience that change in real time, firsthand, the character’s concrete emotion captured on film like lightning in the proverbial bottle. Those types of reactions are priceless, and the camera is often the best tool to translate them.

It is essential to consider the reader’s and viewer’s journeys as they experience the story, and each medium offers its own route. Having said that, I recommend writing the novel version of a script for the story’s sake and the story’s sake alone. Expand your screenplay into a novel by further cementing the story into the world it inhabits.

Every period of time, even if it exists in the future, has sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations that can, and should, be explored and exploited for the sake of strengthening the story. The more you know about the world your screenplay explores, the more it will show on screen—even if what you’ve been exploring happens off-screen.

At the very least, it speeds up the process of directing your actors. What motivates your character, you ask? Take a read through the novel and all your questions shall be answered.

Editor’s note: You can screen No Alternative on iTunes.

William Dickerson

1 Comment

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hey William, Grate post! I agree completely, and tried that technique on my retelling of an Arabian Night tale, “Mellen Water. I can’t wait to buy your book, though as I am visually impaired, I won’t be able to watch the film. Is there a chance you could email me a copy of your script? BJ has my email aadress. Thanks. If your interested in comparing how your process differs from another’s the Maker of “Bridge to Terabithia” made a podcast describing How he went about addapting his mom’s book into a movie.