Independent producer Tom Reed began his studio career at Walt Disney/ Touchstone Pictures during the Katzenberg era where he ran the office of creative administration for the motion picture group. Since then he has jumped from studio features to the low-budget arena and back again, holding Vice President positions in companies as varied as Cinetel Films and Imagine Entertainment. He has been the senior executive at The Jonathan Lynn Company (My Cousin Vinny) and Interplay Entertainment, a computer game powerhouse. He has produced indie films that have screened in competition at Sundance. Tom has also written and directed two short films that have played the festival circuit. He is a writer-centric producer who fully embraces the power of the BS2 and the Master Cat ethos.

Written and Directed by: Tim Burton

Year of Release: 1982

Length: 5:48 mins/secs

Genre: “Out of the Bottle” Fantasy where the mechanism of transformation is a child’s imagination. Secondary genres: “Monster in the House” and “Epic (supernatural/doomed) Love.”

Logline: Outwardly, seven-year-old Vincent is an ordinary child and a model son, but inwardly he’s a tortured artist with a penchant for Vincent Price and Edgar Allen Poe. His rich fantasy life spills into his normal life when he’s sent to his room after digging up his Mom’s garden, but later when Mom urges him to go out and play, the question becomes: will he ever be able to escape the overwhelming power of his imagination?

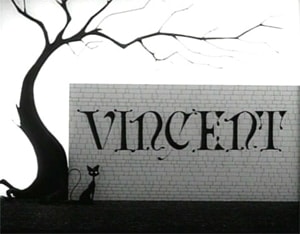

Opening Image (0:00 – 0:37): We see a tree — leafless, twisted, haunted — next to a wall photographed in black and white. Though the birds are chirping, a melancholy flute casts a somber mood. As the word “Vincent” appears on the wall in Gothic script, a spindly black cat crosses the wall and enters the window of a suburban house where we find a boy playing the flute we’ve been hearing. Immediately established is a context of present day middle-class America (the house), and an artistic boy (he’s musical) who’s a loner (by himself in an empty room). Contributing to the feeling that this boy is an outsider is the exaggerated character design (this is a claymation film) which emphasizes his large, sensitive eyes, skeletal arms, and forlorn appearance. It’s almost like he’s a long lost member of the Addams Family, and like the world of Charles Addams, this one already feels both whimsical and vaguely unnerving; a normal world that’s playfully off-kilter. This concept of an ordinary suburban world beset by a lurking intangible strangeness is the central idea of the story and will be immediately expanded upon.

Theme Stated (4:11 – 4:31): This is a short so there’s no “theme stated” up front. That comes later, just where it should, in the context of the B Story. If the theme of a story is what the Hero needs to learn in order to function more successfully in the world, the theme of Vincent is stated explicitly, in dialogue, by the person who’s closest to him: his Mom. In fact, it’s the longest passage of dialogue in the film. But we’ll get to that later. There’s another theme at work here that isn’t expressed in dialogue, but is imbedded in the fabric of the story, and that is the staple theme of the “Out of the Bottle” fantasy genre: “Be careful what you wish for.” Vincent will discover that the pursuit of his goal has unforeseen consequences (or does it?).

Set-Up (0:38 – 0:49): Voice-over narration begins, simple and benign: “Vincent Malloy is 7 years-old. He’s always polite and does what he’s told.” The style is distinctly “Seussian,” and what could be more child-friendly (i.e., normal and safe) than a Dr. Seuss book? Yet it’s spoken by the actor Vincent Price, most closely associated with low-budget horror films, several based on the works of Edgar Allen Poe. Could this be a subtle restatement of the central duality “normal on the outside” vs. “troubled on the inside”? Let’s see…. The cat jumps into Vincent’s arms (“Snuggle with the Cat” sympathy!) as the narrator tells us, “For a boy his age he’s considerate and nice.” That completes the clear snapshot of Vincent’s external world, the status quo of apparent normalcy. Then the narrator says, “But he wants to be—“

Catalyst (0:49 – 1:06): “—just like Vincent Price.” And with that we have the desire-driven goal stated outright. Vincent’s eyes widen and he undergoes his first Transformation (!): he’s suddenly wearing an ascot and smoking jacket, his hair windblown, his eyebrows thick and angular, dark bags under his eyes. He has turned into Vincent Price! He pulls out a cigarette holder, puffs theatrically, and the cat shrieks! Now the central idea of the film is clear, in addition to the promise of the premise: this story will be about the contrast between Vincent’s outward persona in the real world and his dark imagination, literally his “Inner Vincent Price,” and the resulting trouble of the two worlds colliding. The Fun & Games will involve how these two worlds are juxtaposed, to comic effect, and their contrasting visual design. As the tension between the two worlds mount, the central dramatic question becomes which world will triumph? This may be a child’s fable, but it’s about existential angst — which is another way of stating the gloomily humorous premise. Vincent strolls to the door in his smoking jacket, leading with chin and cigarette holder. He opens a door.

Debate (1:07 – 1:13): This is a short film so there’s no debate. Vincent never doubts or questions his journey, not, that is, until he’s in the throes of the Finale (and even then there’s room for doubt). His interest and mission is to spend as much time in his internal world as possible, though the external world often intrudes, like now. Vincent enters another room, but from this side of the door he’s suddenly a seven-year-old boy again, “normal Vincent” back in suburbia (Transformation!). The Narrator notes that Vincent “doesn’t mind living with his sister, dog and cats…” – and we see these characters through Vincent’s eyes (they all appear slightly deranged, especially the sister). The Narrator continues: “…though he’d rather share a home with—” – and then Vincent switches off the light and the screen goes black.

Break into Two (1:14 – 1:46): As the Narrator says “—spiders and bats,” an overhead spotlight reveals Vincent in a pool of light, dressed in a white laboratory coat and black rubber gloves, in full “Vincent Price Mad Scientist” mode (Transformation!). The location has made a significant shift, too — we’re no longer inside Vincent’s house; we’re in the “lair” of his internal world, his dark imagination, and rarely has there been such a magically macabre “upside-down funhouse-mirror world” than the one depicted here. This is Dr. Seuss by way of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari — on a cocktail of steroids and LSD — and its blend of whimsy and horror strikes the perfect mixture of twisted, surreal giddiness time and again, bursting with Fun & Games visual and aural detail. Part of the Fun & Games, too, is the array of visual references piled on top of each other with ever increasing density, images that draw from the annals of horror in storybook, literature, and film, from Grand Guignol to Roger Corman, and even Surrealist painters Magritte and Dali. We see Vincent interact with various monstrous inventions, and then swoon along a corridor, as the Narrator tells us, “There he could reflect on the horrors he’s invented, and wander dark hallways alone and tormented.” Click. A light turns on.

B Story (1:47 – 2:05): Vincent is back in the normal world again (Transformation!) where he finds himself leaning against the leg of a fat lady in a floral print dress. The B Story here involves the characters in Vincent’s real life that he encounters and incorporates into his morbid fantasies, specifically his Aunt, Dog, and Mom, in that order. The Narrator tells us that “Vincent is nice when his Aunt comes to see him,” underscoring again the seeming normality of his outward persona, but then, in a single cut (without the transitional device of the light switching off or on, which amounts to a stylistic escalation) he’s “Mad Scientist Vincent” again (Transformation!), and we see the following action described by the Narrator:

Fun & Games (2:06 – 2:29): “…but imagines dipping her in wax for his wax museum.” Vincent activates a contraption that lifts his Aunt, the fat lady, and drops her into a vat of molten wax. It’s designed and presented with sinister relish, much like all the Fun & Games of this sequence and the film as a whole. From this point forward, everything we see in Vincent’s internal world is progressively magnified — his fiendish attitude and appearance, the design of the sets, the extreme Chiaroscuro lighting, the music and sound effects, and the cleverness of the transitions from one world to the next — such that even in the absence of external conflict (Vincent is going about his grisly business unopposed here, which is appropriate since it’s his fantasy), there is nevertheless a clear and vivid escalation of visual and conceptual expressiveness. Nothing threatens Vincent here, but things get more dramatic. There’s a build, a progression. Much like Mickey’s fantastical dream during the Fun & Games sequence in “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” Vincent is in charge and everything is just as he wants it to be. Vincent is happily living his twisted dream, and as Blake would say, the story is delivering on the Promise of the Premise.

The sequence continues as Vincent experiments on his dog “Abercrombie” by zapping him with electricity that results in an explosion, and when the smoke clears we’re in a new location of German Expressionist surreality where Vincent and his now zombiefied dog can “go searching for victims in the London fog.” A Fun & Games detail (that also functions as fore-’shadowing’ [F&Gs!]), Vincent’s own shadow is a monstrous Seussian ogre.

Another verse of narration and the accompanying visuals complete the detailing of Vincent’s inner world: “His thoughts weren’t only of ghoulish crime. He likes to paint and read to pass some of the time. While other kids read books like ‘Go, Jane, Go,’ Vincent’s favorite author is Edgar Allen Poe.” Two new narrative threads are introduced here: 1) we see Vincent painting a portrait of a woman we soon discover is “his wife,” and 2) Edgar Allen Poe is invoked. From this point forward these two elements will take center stage as Vincent’s world becomes a nightmarish Gothic Horror Romance resulting in the inevitable insanity so often alluded to in Poe’s demented universe.

Midpoint (2:30 – 3:10): At the Midpoint “stakes are raised and the Hero squeezed,” and that’s exactly what happens here as a new and very specific problem is introduced: Vincent, while reading Poe, gets it in his head that “his beautiful wife had been buried alive!” (the theme of being buried alive is a recurring motif in the work of EAP). Vincent is a Dude with a Serious Problem, and, now that he’s smelled this “whiff of death,” he takes action in the real world. We’re suddenly at a gravesite, at night, and Vincent is shoveling to the depth of a casket, when—

Bad Guys Close In #1 (3:11 – 3:22): Transformation! In a match dissolve we transition to daytime and Vincent, a normal boy again, is revealed digging up the flower garden. His Mom’s legs enter frame and we can tell by her stiffly pointed finger she’s none too pleased. The Narrator tells us, “His mother sent Vincent off to his room.” Perfectly in keeping with the “Bad Guys Close In” story beat, the moment Vincent pushes the external world, it pushes back, and there are immediate consequences. The price Vincent pays for acting on his imaginings is rendered by a dissolve to a tortured staircase that looks like a set of monster’s teeth, with little Vincent ascending it in desolation (Transformation!). Narrator: “He knew he had been banished to the tower of doom.”

All Is Lost (3:23 – 3:34): Once inside his room (his “Price-ian Lair”), he broods beneath the portrait of his wife as the Narrator explains “he was sentenced to spend the rest of his life alone with a portrait of his beautiful wife.” Vincent breaks down in grief. The “whiff of death” is revisited, but with increased intensity. On top of that, much like “his wife,” Vincent is now incarcerated himself, a parallel that’s suggested when the Narrator says, “While alone and insane encased in his tomb…” Vincent’s room is a tomb. He’s buried alive! More death, more E.A. Poe, more Fun & Games!

Bad Guys Close In #2 (3:35 – 4:03): The door opens and Vincent’s mother bursts into the room, bringing us back to the normal world again (Transformation!). The Narrator speaks for Mom when he says, “If you want to you can go out and play. It’s sunny outside and a beautiful day.” Mom shifts from being an oppositional authority figure meting out punishment back to a loving Mom who wants the best for her son. This is a reversal for the better, at least from the point of view of the external world. But Vincent is now firmly in the grip of his interior world, deeply engaged in his tortured imaginings. And since we know that (so far) he likes this — that he apparently prefers residing here than in the “real world” — then he’s not eager to leave it. From that perspective Mom is still a “Bad Guy” exerting oppositional pressure by asking him to go out and play, so we have the BGCI beat repeated. However, she doesn’t demand that he go, she simply gives him the choice and exits, which immediately thrusts us out of Vincent’s bedroom back into his “Price-ian Lair” (Transformation!) allowing his psychodrama to continue. Vincent clutches his throat and gropes for a quill pen as the Narrator says, “Vincent tried to talk but he just couldn’t speak, the years of isolation had made him quite weak. So he took out some paper and scrawled with a pen—“

Dark Night of the Soul (4:04 – 4:08): If the “Dark Night of the Soul” is the realization of the Hero’s worst fears, then this beat qualifies with flying colors. As we see an extreme close-up of Vincent’s orb-like eyes that glow suddenly bright, with animated concentric circles emanating outward (with eerie sound effects), the Narrator, as Vincent, proclaims, “I am possessed by this house and can never leave it again!!” The Hero’s dream has become a nightmare. But when your dream is nightmarish to begin with, where else is there to go but straight to Hell? Is this the terrible truth Vincent has just glimpsed? Or is he having the time of his life?! It’s impossible to say. Loss of sanity, mental anguish, and spiritual annihilation are recurring themes in the work of Edgar Allen Poe, and all these themes are fully embraced here (Fun & Games!), both conceptually and expressively – and extended straight out to the audience.

Break into Three (4:09 – 4:33): A and B Stories merge as the door opens and we transition back to the real world once more (Transformation!). Mom enters and delivers the Theme Stated, in no uncertain terms: “You’re not possessed and you’re not almost dead. These games that you play are all in your head. You’re not Vincent Price, you’re Vincent Malloy. You’re not tormented or insane, you’re just a young boy. You’re 7 years-old and you are my son. Now I want you to get outside and have some real fun.” This is clearly the solution to Vincent’s dilemma (if he actually has one!). Will he act on it? Mom leaves again, and when she shuts the door the room is plunged into inky blackness.

Finale (4:34 – 5:16): From black, Vincent backs into a harsh light and we’re inside his nightmarish internal world again (Transformation!). But now he appears truly horrified by all he sees. In classic story convergence, the narrative threads featured thus far in his internal world are revisited, but in far more extreme and terrifying ways, rising to the fever pitch of a lurid, malevolent, oppressive, hallucinatory phantasmagoria (yes, all those big crazy words apply and it’s all part of the Fun & Games!). The house of Vincent’s mind is filled with Monsters (MITH)! “The room started to sway, and shiver and creek. His horrid insanity had reached its peak.” The visuals here are dominated by insanely exaggerated German Expressionism — cockeyed angles, twisted checkerboard patterns, funhouse mirror distortions — all at a breathless pace, with every tool of filmmaking employed with gusto. “He saw Abercrombie, his zombie slave, and heard his wife call from beyond the grave, she spoke from her coffin and made ghoulish demands, while through cracking walls reached skeletal hands…” Vincent recoils in horror from images of the Seussian ogre, his mad wife, disembodied skeleton hands and a 15-foot tall figure of his Aunt that melts in a tsunami of liquid wax and sweeps him into a swirling vortex. “Every horror in his life that had crept into his dreams swept his mad laughter to terrified screams!” He opens his mouth impossibly wide and we fly inside and enter a field of blackness where a warped door floats in space (classic Surrealism). Vincent enters the scene, groping against gravity for the handle of the door, but he falls “limp and lifeless down on the floor.”

Final Image (5:17 – 5:48): As Vincent lays there he reaches for his throat, and we’re told “His voice was soft and very slow as he quoted ‘The Raven’ from Edgar Allen Poe.” The camera begins a long, slow pull back that lasts nearly 30 seconds (the longest single shot in the film) as our Narrator, Vincent Price intones, “And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor shall be lifted…” — (and by this time, little Vincent Malloy is a mere speck of white in the enveloping sea of dark — and the light blinks out. Blackness. Over this, the last word is uttered): “Nevermore.” Fade out.

The melancholy flute from the opening is reprised over 37 seconds of tail credits. The story leaves us wondering, has Vincent truly lost his mind, or is this his idea of ecstasy? Or is it both? We’ll never know for sure (“Be Careful What You Wish For!”), but the music suggests that Vincent may have at least recovered enough sanity to pick up the flute again. Fun & Games!!!

Comments: This film is a tour de force. Who knew so much narrative invention could be packed into 5:48 mins/secs? To focus just on the story construction for a moment, it precisely follows the BS2 Template (consciously or not), so its “skeleton” (to be T-Burtony about it) is perfectly intact. In fact, every single frame of film, every single choice is part of a BS2 story beat. Possibly the most constructive thing I’ve learned from an immersion in Blake’s teachings and applying the BS2 as a tool to examine stories is the concept of Fun & Games/Promise of the Premise, and I think its power as a storytelling tool is enhanced the more it’s used, the more it infuses the entire story, as it’s done here (and in Frankenweenie) rather than a single sequence. The best films tend to do this. But it can’t be done without having a firm grasp of the story’s organizing principle.

In the case of Vincent, what organizes it is the main character himself, a boy. Everything is filtered through Vincent’s seven-year-old consciousness, and that motivates the Dr. Seuss voice over storytelling device, it gives license for the progressive visual/cinematic exaggeration that Tim Burton uses to such powerful effect, it even makes palatable the expressly stated theme in dialogue, coming, as it does, by way of a mother’s admonishment. Secondly, the organization comes from the Hero’s specific personality: he’s a tortured artist, a proto-Goth with an affinity for existential darkness. His internal world is dominated by Vincent Price and EA Poe, and through them, the entire history of horror and morbidity in the arts can be (and pretty much is) touched upon by the storyteller.

Tim Burton knew his subject matter well. The array of references is astounding, and the “sinister relish” of the filmmaker is palpable. This film is a tremendous ode to the power of the playfully morbid imagination, not just on the story level, but in every aspect of the filmmaking art — the character design, sets, lighting, effects, editing, and music. Factor in that it’s all pretty much the work of just one guy, well, it simply boggles the mind, as great Art should do. Vincent is a supremely entertaining, ultra-conscious, and organic work of cinematic art that expresses a signature personal style. It didn’t win an Oscar, but it should have. It’s a masterpiece. Thankfully, it helped launch the career of one of the most original and accomplished artist/filmmakers working today.

Next week’s blog: The Fighter Beat Sheet

Tom Reed

7 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

It’s actually The Sorcerer’s Apprentice as if told by Edward Gorey. The rhyming narrative is highly reminiscent of Gorey’s work, especially, but certainly Charles Addams and a couple of other 20th century artists influenced this short. I love how it’s the MITH genre but the house is his skull.

And he’s not a “proto-Goth.” He’s what we call a “baby bat.” ;)

No subgenre? Just some sort of out of the bottle?

Why do beat sheets posted here always choke with the genre?

A complete beat sheet includes genre and subgenre. But it always seems like an afterthought here…

Hi William ~

Huh? If you read Tom’s eloquent post, you would have seen that Tom, in the subject line “Genre,” did indeed include not one sub-genre, but two.

Blake and STC! have never claimed that “a complete beat-sheet [always] includes genre and sub-genre.” If you have ever studied in person with Blake or the other Master Cats, you would realize that this assumption is a complete fallacy. There are countless stories out there that stick to one specific genre; there are also those that weave in one or more sub-genres. VINCENT is a fine example of the latter.

However, as you seem to have issue with every beat sheet posted, perhaps a proactive and positive approach would be for you to submit your own beat-sheet for consideration of publication. This project would be an interesting challenge for you to take on, and a way for you to publicly demonstrate your comprehensive knowledge of the Save the Cat! principles of story structure, rather than to limit your remarks to attacking the hard work of others.

Tom, again, I curtsy to you. What an engrossing and well-told tale – through a beat sheet! I feel as if I’m sitting in a darkened theater, watching this Gothic fable unfold before my eyes. Wonderful visuals; expressive tones. Thank you so much for sharing your vision – and your wisdom – with us. What a beautiful, beautiful post.

Genre: “Out of the Bottle” Fantasy where the mechanism of transformation is a child’s imagination. Secondary genres: “Monster in the House” and “Epic (supernatural/doomed) Love.”

William, this isn’t good enough for you? A primary genre — with an explanation, plus 2 secondary genres. For a film that’s less than 6 minutes??

What would you prefer?

Thank you, Annie, for your eloquent defense and praise. I was worried it was too long and too exhaustive, but as I got into it I realized that so much of the story was told through voice over that I had to include that; a fateful decision that added length but also precision. I’ve done three of these now; one short with no dialogue or voice over (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), one short with voice over (and some dialogue by way of voice over — this one) and one short that has conventional dialogue and no voice over (Frankenweenie, not yet posted). It was an examination of how the contrasting stylistic choices (silent vs. voice over vs. conventional dialogue) might affect structure, if at all. My conclusion is that structure is present, or not, irrespective of such choices. In any case, as to the above, I’m not even sure what William is getting at — it’s like he didn’t even read it. So easily ignored. I see that you have a blog. I’m going to check it out. Thanks again for your acknowledgements.

Tom

Why didn’t you answer my comment?

Michael, are you referring to your comments on THE FIGHTER beat sheet? Anne answered those in that Comment section.