Master Cat! Tom Reed relates why Argo is a story that resonates:

I don’t know anyone who’s seen Argo that didn’t love it. I loved it even more the second time. Yeah, I saw it twice, something I rarely do nowadays. I think it’s flawless. And when a film is flawless I try to figure out why, a process that begins by measuring it against the BS2. It’s no surprise that Argo is a perfect fit, scene for scene, beat for beat. But rather than doing a full-blown BS2 analysis (something I hope somebody else does), I’d like to focus on the big picture. Argo gets it right from the outside in, from the broadest strokes to the smallest details.

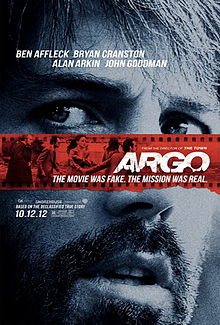

The movie is based on a true story about a mission impossible given to a CIA “exfil” specialist (an expert in getting people out of dangerous countries) to save six American Foreign Service staffers hiding in Iran after the fall of the Shah. The genre, easy to spot, is right there in the premise: this is a Golden Fleece story involving a road (to Iran and back), a team (Ben Affleck’s allies in the spy world, in Hollywood, and in Iran) and a prize (the successful escape). Since it requires intricate planning it’s technically a caper, making this, in Blake Snyder terminology, a classic Caper Fleece.

There are a couple of things immediately impressive about Argo. First, there’s an incredible amount of tension right from the very beginning. It’s very clear that the stakes are life and death, not in a comic book superhero kind of way (such as in a James Bond or Ironman movie), but in a visceral, plausible, and historically accurate documentary kind of way. If caught, these six Americans will be tortured to death at the hands of the Iranian Guard, an eventuality made crystal-clear by the violent demonstrations of Iranian mobs and the palpable fear of the Americans in hiding. It amazed me how intensely real – and intensely threatening – all of this felt. I almost forgot movies could do this.

Juxtaposed against this Primal Threat is the absurdity of the plan devised to address it: “The Hollywood Option.” Ben Affleck creates a fake cover story whereby he is the producer of the sci-fi extravaganza “Argo” (the faux film-within-a-film) and the six Americans in hiding are part of his film crew. He flies into Iran alone on a “location scout” and intends to fly out with them, expertly manufacturing the deception. This is such an absurd scheme that audiences probably wouldn’t swallow it unless it really happened, but the beauty of the story is it did – and it actually worked.

This is in fact the Fun and Games and the Promise of the Premise of the film. Not only do the filmmakers get to make plentiful inside jokes about Hollywood, which they take full advantage of through two fabulously Fun and Gamesy comic characters played by John Goodman and Alan Arkin, but on a more serious level they get to compare Hollywood with the CIA, both industries essentially based on the con. Making movies and going on missions are both Funhouse Mirror Worlds; it’s the circus, a point Ben quietly makes in the closing minutes.

This parallel is expressed in dialogue much earlier, in a scene between Ben and Alan Arkin while eating tacos on the back lot of Warner Bros. Ben asks Alan why he only sees his daughters once a year. “I was a terrible father. It’s a bullshit business. It’s like coal mining. You get home, you can’t wash it off.” This is one of the Themes Stated, and not only does it draw a powerful parallel between The Industry and The Agency, but it draws a more important one between Alan and Ben on a personal level: Ben is separated from his wife and missing his son terribly, and the implication is that the separation is the direct result of his profession which not only requires him to routinely lie, but by being a field operative, requires him to put his own life at risk time and time again (unlike a Hollywood producer who only thinks he’s ever in danger, or a hero). These parallels help bind these two disparate realms together without undermining the fundamental comic opposition – the best of all worlds.

The filmmakers employ an additional strategy to fuse the two worlds together, and this happens almost invisibly. It’s found in the subject matter of the faux film-within-a-film, “Argo” itself, which is a space adventure about revolutionaries standing up to evil and saving their world. Ben’s son is a science fiction fan so he’s linked to “Argo” by virtue of his interest in the genre. But the Iranian Guard, the primal threat to Ben and the six Americans, is also linked to it by virtue of its self-perception as a revolutionary force fighting for a just cause, and this personal identification helps sell the deception at the crucial moment (though I would have liked to see this beat hit just a bit harder). The same thing goes for Ben, the CIA, and the whole Carter administration, who also see themselves as the good guys fighting for a just cause and saving their own. Everyone links to “Argo” – especially Ben.

The pretend world of “Argo” is a metaphor for Ben’s life; Ben himself is the closest thing to a superhero as can be found in our world. This points to an additional genre coexisting with the Caper Fleece in this movie: Superhero, specifically the subset Real-Life Superhero. Ben’s exfil expertise gives him his special power, his nemesis is whomever he’s trying to deceive (in this case, the Iranian Guard), and his curse is the toll this job takes on his wife and son. Multiple genres can certainly coexist in movies, but it’s always better if they coexist seamlessly, as they do here.

Once Ben is in Iran and ready to execute his mission, he’s asked to abort, which would result in the almost certain deaths of the six Americans. Ben refuses, telling his boss, “We’re responsible for these people,” (the second Theme Stated) to which his boss – the Company Man (you can’t make a movie about the C.I.A. without tipping your hat to the Institutionalized genre) – responds like the bureaucrat that he is: “We’re required to follow orders!” Ben reluctantly agrees, but after his Dark Night of the Soul he has a change of heart (Transformation!), reclaiming his Superhero identity and his mission. He calls his boss and says, “I’m responsible. I’m taking them through.” At that point his boss, unwilling to leave his agent “at the Tehran Airport with his dick in his hands,” has a similar change of heart (another Transformation!) and goes to similarly heroic lengths to help assist his friend from afar.

Act 3 is an incredibly taut race against the clock, the allies working together with split second timing, the Opponents a mere half-step behind. It’s a procedural of escape that expertly interweaves the primary story threads in a monumentally tension-filled Five-Point Finale that results in a mythic last-second victory. One of the masterstrokes of the movie is it manages to accomplish all this while maintaining its tone of absolute credibility. Like I said, this isn’t the universe of the comic book superhero, even though one strand of its DNA originates in the Superhero genre. The other masterstroke is that the Fun and Games never undermines the threat, or the credibility, for that matter. Everything is perfectly modulated. An amazing achievement.

At the end Ben reunites with his family. It’s too late for Alan Arkin to do so, but not Ben, who’s still young enough to learn. Ben keeps one of the storyboards from the faux “Argo” and gives it to his son, which we see in the final shot: it’s a panel depicting the hero of “Argo” escaping danger with a boy (presumably his son) at his side. The Opening Image of Ben in Argo showed him in his disheveled bachelor’s apartment, asleep in his clothes, his life a mess, isolated and alone. The Final Image is a perfect bookend, proof of change and Transformation: Ben has resolved his dilemma – he has reclaimed his superhero identity by saving the six Americans (and completed his journey home with his fleece intact), and he has also renewed his commitment to his family.

From now on he’s going to be there for his son, who at the end we see asleep in his arms. And ironically, nobody will ever know about his superheroics – not his wife or son, not Alan or John’s Hollywood cohorts, nobody – because the mission must remain classified. And sometimes that’s just how it’s got to be – the Superheroes among us must remain anonymous. I know, it hurts. Especially in Hollywood where everyone wants credit.

Tom Reed

12 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Nice beat sheet on ARGO. I loved the film, want to see it again. I particularly loved the “references” to Hollywood, most of the audience laughed at the negative downplay of Hollywood and how cavelier they were and it rang true, but in the end the Hollywood movie within a movie rang true, came through and saved the day. It kind of made you proud to work in Hollywood.

Excellent analysis, Tom! Great inspiration for tweaking my own Historical Event, Action script, RECKLESS WHEELS. Thanks.

Excellent analysis and thanks.

The only serious criticism I’ve heard on this script came from a viewer who is not a writer, and I have to agree with her. Tacking the broken family backstory onto Ben’s character, even though theoretically sound and surely believable (as you have well pointed out), came off as a bit too much.

That story element makes sense when you look at it purely from a writerly point of view, but on screen it felt a little forced, a little tired, and even unnecessary. A case of viewer experience trumps theory here?

Hi Frank. You make such an interesting point that I wanted to chime in. As I was watching it the first time, my feeling about Ben’s personal problem, that whole family subplot, was that it seemed a little thin as it was unfolding, a little underexplored, perhaps. That is, I thought that up until the scene with Alan Arkin which allowed me to see into Ben’s issues in a really significant way. Though granted, it’s subtle. It’s the bare minimum. Some people, like the person you referenced, might feel more is needed, or think that if it’s not fully explored then it’s extraneous, tacked on, and maybe manipulative, or whatever. From my own perspective as a viewer, everything came together at the end — Ben showing up at his home, getting hugged by his wife, scarcely a word between them — I think he asks, “Can I come in?” And I don’t think she says anything. So again, the approach is subtle, unforced, and perhaps underwritten. But when we finally see that panel of artwork on his son’s shelf, and it’s of a man and a boy — only minutes after seeing Ben’s son asleep in his arms — well, I don’t know about you, but I was verklempt! I think I was kind of noisy about it, too. So it TOTALLY worked for me. At that point, any thought of it being underwritten, or forced, or not working, completely disappeared. For me, the theory in practice was utterly effective. But this is an art form, and it’s about emotion, and paying attention, and all these are huge variables and no two audience members are exactly the same, and sometimes effectiveness simply comes down to personal taste. My guess is your friend has a unique taste, but it’s not necessarily the mainstream. I think the way it is works for a mainstream audience with mainstream tastes, and exceptions in no invalidates sound theory. After all, it would be impossible to please everybody. That’s what makes it the movies!

Great to see genre listed along with the subgenre. So many people list all the beats out and never even mention the BS genre…

Well done! Great to see a thorough discussion of any film! :)

– wil

Fantastic analysis! It’s great to watch a movie that works on so many levels, when so many things could go wrong and make it a dud. Reading your analysis of why it works so well is fascinating. Thanks for posting!

Thanks for a brilliant analysis of a fabulous film.

I loved Argo, too, and thought Affleck was especially brave (and generous to the other actors) to play down his character. In an interview, Affleck says he consciously decided to do it this way as the real Mendez is very contained.

I thought the part with the kid was very effective. Yes, we all know what the writer is doing, but fatherhood is a theme that affects us all, and it was just enough. Same with the nail-biting finale. We all know we’re being played like a violin but the musician is so skilled that we don’t mind.

Speaking of “music”, I loved the film so much that I even bought the soundtrack by Alexander Desplat. The third song is called “Scent of Death” which immediately made me think of Snyder’s “whiff of death”. And it comes at just the right moment in the film. I was tempted to beat out this marvellous film using the soundtrack titles, but it might not have worked as well in practice as in theory.

Besides, you’ve done it so much better than I ever could, Tom!

I can’t wait to read your next analysis.

Now that I have seen ARGO, I would like to comment on it. Right – it is quite a good film, but I think it has more to do with its subject matter than the quality of the script. The basic dramatic situation is so threatening, that no screenwriter and no director on this planet could completely screw it.

Basically I was afraid this would be just another american propaganda film against all the bad muslims out there in this world. The timing of this film could not be any better for that. So maybe ARGO as a film is just exactly what its story is about: a CIA project. …. But I think the film is pretty balanced and merciful on the Iranians side. It could have used the opportunity to dwell more on that conflict, but it did not.

I think, the script as well as the directing are only 70% —

Too many close-ups destroy the rythm of scenes and the whole movie. It´s always the same shot size with these new directors…. Spielberg would never do this.

But the main weaknesses are in the script for me: I think it is problematic, that the characters of Arkin and Goodman almost disappear during the second act, just to be ressurrected for that one important phone call. The phone call scene in the end feels pretty constructed and forced just to evoke the final suspense.

Another problem: I could never really relate to the hostages. They remained strangers. That is quite a problem in a film, which is supposed to make me worry about them. Not that I was not hoping for their rescue. They just never really became characters for me which takes from the movie-pleasure of watching them impersonate a film crew.

Another point: Compared to the relevance of the subject (relationship of Iran/America) there should have been at least one scene, in which an “American” and an “Iranian” talk about the political situation and their different motivations. Just like in “Munich”. Otherwise the political situation in Iran just remains a cliched movie background for creating quick threats and bad guys.

Another point: Affleck did not have one scene with his wife at the beginning of the movie. So the whole private story of his remained purely hypothetical. I could not really feel his relationship problems. Hence the scene with his wife at the end kind of felt unearned. That might be the reason, why some people think it is a bit pathetic. I believe, if that problem would have been granted more screen time, it would not feel forced. You must show problems like that in scenes, not just in dialogue. E.g. the “television”-scene with the son was pretty good. Two things in one: relationship story and inspiration for the rescue plan.

Next problem: Affleck´s character lacked humor which made it hard for me to follow him as the protagonist. He could have been a little more cynical and less self loathing. He keeps the same facial expression thoughout the entire movie, which is kind of — unrealistic?

He also never has a profound or meaningful exchange with the hostages whose lifes he is supposed to save… – so why is he so eager to do it. Schindler had his Stern. No real connection between these characters occurs. That is not good screenwriting.

And the line “Argo fuck yourself” should have been the last line in the film.

Well now – I am curious about comments.

One more thing: I don´t think, ARGO is a bad film. It is a good film. Especialy compared to all the other mindless crap that just floods the theaters. I just think, it could have been much better in regard to its basic premise and subject matter. A real comment about the actual situation and not just a suspense thriller that could have taken place anywhere.

Tom,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about the protagonist’s family sub-plot, and also how it affected you personally as a viewer. When I movie makes me choke up, I send a little thank you out to all involved. That’s a little more life I get to live.

I have one other idea here. I agree with you that the the sub-plot holds together as such. And it is quite deftly handled (the parallel with Lester Siegel’s family story). But I think I see another reason why it’s not touching some viewers, and still feels to me a little tacked on to me.

It doesn’t express a character arc that intersects well with the A story.

This thought reminded me of the only other beat that I thought fell short (by just a smidgen) in the film. When Mendez reverses his decision to go along with the operation’s cancellation, in his hotel room. It’s a powerful decision, no doubt. Meaningful and difficult. But from purely a story angle, it would have worked better if it had expressed a turning point in the character’s journey as a man. In truth, it would have been more surprising in Mendez left the hostages behind, wouldn’t it? That speaks to how it wasn’t really a wrenching decision for him.

And here’s the thing–if Mendez’s personal journey (whatever it might have been) and that turning point action could have underlain, somehow, the healing that lets Mendez back into his ex’s life? Perfect. That would have done it for me. That would have been an ideal integration of the family sub-plot.

I think the problem here was perhaps that Chris Terrio was dealing with history, and with a real person. You can only go so far with molding a character ideal to a story while remaining faithful to the facts, yes?

Thanks again, Tom, for the great analysis, and for giving me something to think about.

Best,

Frank

Frank, I thought it was the same issue in Moneyball – if you’ve seen that film. You have those relationship scenes between Brad Pitt and his daughter, and they never get connected with the main story or themes. And just like in Argo, that’s what the film chooses to close on, even though it was tangential all along.

But I think it’s worse in Moneyball for two reasons:

1. After having questioned a number of things about the game, about winning & losing, and the decision of whether to move to bigger stakes and bucks… the movie resolves all of this (actually doesn’t) with that father/daughter sidestory providing the full motivation for what the main character decides!

2. Pitt’s character is sort of an asshole to everyone throughout, and to me, those scenes with his daughter were extremely manipulative in that they were there, I felt, simply to make Pitt more likeable.

Thank you. Your blog is enlightening. Also, Oliver’s comments were satisfying to me as I landed on your site by googling “I did not feel connected to exfils”. An audience needs ‘to care’ about the characters–an early lesson in acting (and directing, I suppose, also). I wanted to feel more for the exfils and did so only later as a result of a documentary and the special feature on the dvd. Keep Packin’ Lite,

Patriczia, author

Send Lite to Every Fear: The Everyday Hero’s Litany

Good review, other than a horrific overestimation of the ending. Far from flawless, Argo commits one of the most comical endgame mistakes in recent memory, staging a ridiculous beat-up-truck-full-of-bad-guys vs airliner race finale that is beyond a joke. I understand the need to drive a good finale, and the truth of the (real life) story is that there was no climactic confrontation, which certainly won’t drive ticket sales. That said, cars chasing planes has been and will forever be the one of the most ridiculous tropes committed to film stock.