Oppenheimer is a visually stunning film. Director Christopher Nolan provides an unforgettable depiction of the atomic bomb’s otherwise unimaginable power, masterfully composing images affecting enough for The Atlantic to publish an article entitled “Oppenheimer Nightmares? You’re Not Alone.” In it, viewers describe the terrifying scenes their own psyches generated to match the ones served to them by Nolan.

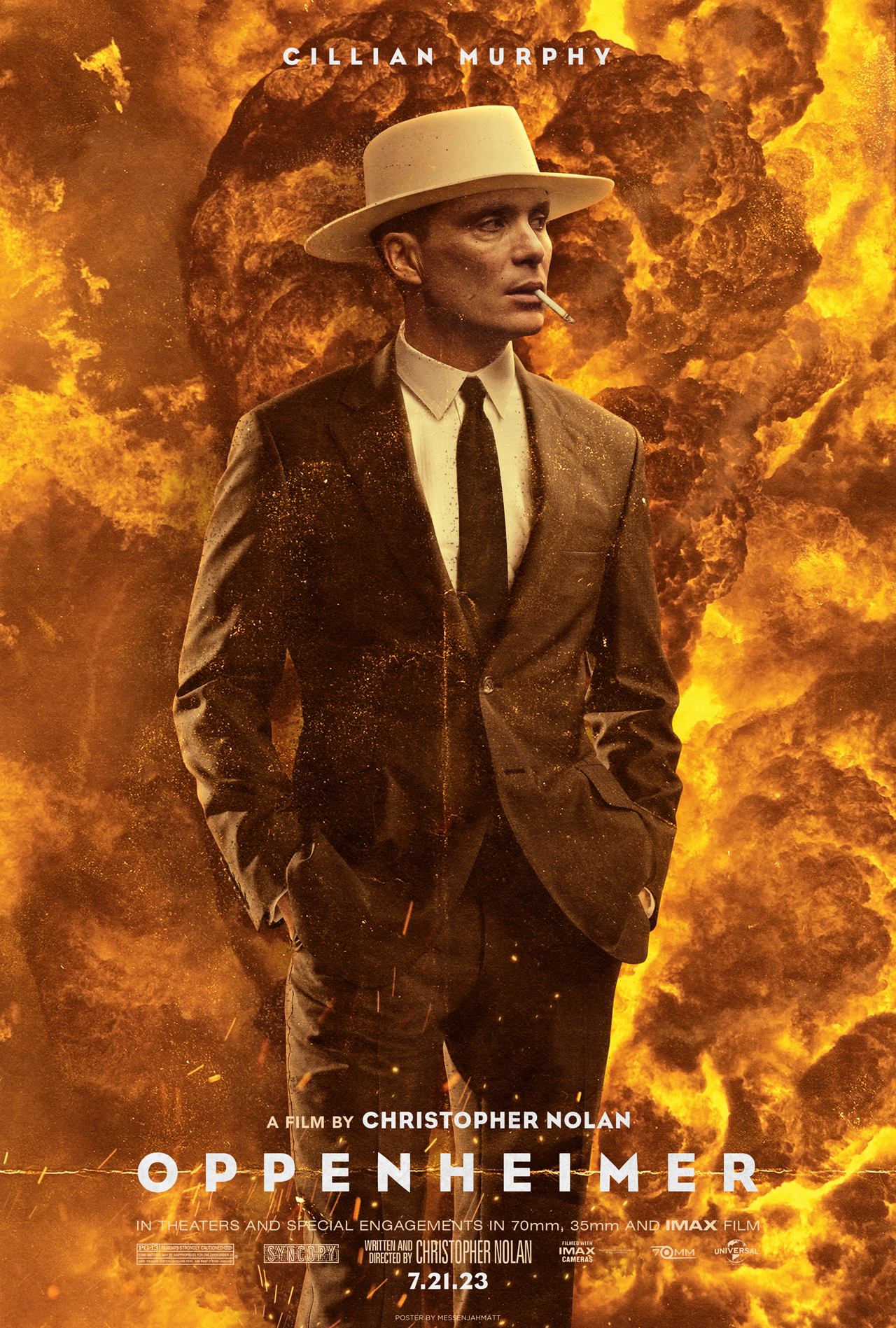

Also memorable are the visual details of Cillian Murphy’s meticulous characterization of the physicist, including his gaunt, drawn face (the product of an extremely restrictive diet undertaken by Murphy) and his trademark hat—a kind of fedora/porkpie hybrid. And another item that had particular resonance with me: a seemingly ever-present cigarette.

I read somewhere that Oppenheimer smoked Chesterfields. I smoked Marlboros. And even though I quit more than 25 years ago, the sight of someone enjoying a cigarette can still stir a faint craving. I loved smoking—I loved everything about it, and I sometimes miss it, even though I’m certain that quitting was perhaps the best decision I ever made.

And why did I start? Well, that’s complicated, but I’m sure that part of the reason was the many positive things I associated with cigarettes. I was born at the end of the Baby Boom and the culture was still filled with powerful messages about smoking. In the preceding decades Hollywood developed an iconography of glamour, strength, and sophistication that included cigarettes. Films presented endless variations of manly Humphrey Bogart lighting alluring Lauren Bacall’s cigarette before firing up his own.

As a young teen in the 70s I wanted to emulate Bogart’s successors. I went to the movies and saw handsome actors playing powerful protagonists who smoked their way through some of the most successful films in American cinema. Consider some memorable scenes from films Blake Snyder references in Save the Cat!:

A cigarette dangles from the mouth of Chief Martin Brody (played by Roy Scheider) as he chums the water in the Monster in the House classic, Jaws. He’s muttering disgustedly about his foul chore when the beast suddenly rises up. He jerks back, terrified. The cigarette is still dangling when he staggers back into the pilot house and tells Quint (Robert Shaw), “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

We watch Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) sacrifice his own identity for the good of the group in The Godfather, which Blake tells us is typical of the Institutionalized genre of storytelling. As head of the family, Michael systematically eliminates all its rivals, growing it into the country’s largest criminal enterprise.

In The Godfather Part II, Michael is challenged by a seemingly unbeatable adversary in the form of a Senate investigating committee. He sits at the witness table armed only with a pack of Camels and an ashtray, prepared to turn back this existential threat to everything he has sacrificed so much for.

“Is there any place you don’t smoke?” asks Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) of Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) in All the President’s Men, one of my favorite examples of the Whydunit genre. We have watched the two of them struggle to find a motive for the Watergate crimes, surviving on little sleep, a fast-food diet, and, in Bernstein’s case, an ample supply of nicotine.

The message I got from these films and countless others was that any formula for success in life includes a pack of cigarettes. They were an essential part of one’s survival kit and a well-earned reward for anyone who prevails against long odds.

Still, it would be wrong to say that I started smoking simply because of the images I saw. Millions of my peers were exposed to them, too, and never decided to light up.

This essay is not meant to add anything to the formal scholarship devoted to finding a correlation between the images we see and the choices we make. It’s only an anecdote with a simple message: images, particularly in the hands of talented creatives, have enormous power—the power to terrify us in the middle of the night, or simply to activate a long-dormant craving.

In 1970 Richard Nixon signed legislation banning cigarette ads on television and radio. It was the beginning of an ongoing effort to turn back the tide of pro-smoking images that flooded American culture, from billboards to Oscar®-winning films. In 1988 the tobacco industry established a voluntary ban on cigarette product placement in US films, and the practice was officially banned by the 2009 Tobacco Control Act.

But regardless of the reasons why I started smoking, I was ultimately responsible for choosing to quit. And I think responsibility is the key word.

Oppenheimer was said to have smoked as many as 100 cigarettes a day. It would have been absurd for Nolan and Murphy to ignore that fact. But I believe filmmakers are obliged to remember the power of images and should continue to ask themselves if a particular depiction of tobacco use is really necessary.

Robert Oppenheimer died of throat cancer when he was 62. Next year, the last of the Baby Boomers (including this one) will turn 60. More thoughtfulness about how smoking is depicted might help some of us, as well as future generations, enjoy the gift of longevity denied to the man at the center of this remarkable film.