Written and Directed by: Leonardo Matsuda

Written and Directed by: Leonardo Matsuda

Genre: Just as with Inside Out, this film has elements of two genres. As a Buddy Love story, the Brain is an incomplete hero that must learn to find balance with its counterpart… but there’s a complication as the two struggle over what their host wants and what he needs. As a Rites of Passage story, the Brain faces the life problem of trying to control the Man’s every action, but does so in the wrong way until it faces acceptance of a “third way” during the Dark Night of the Soul. What do you think? Sound off in the comments below!

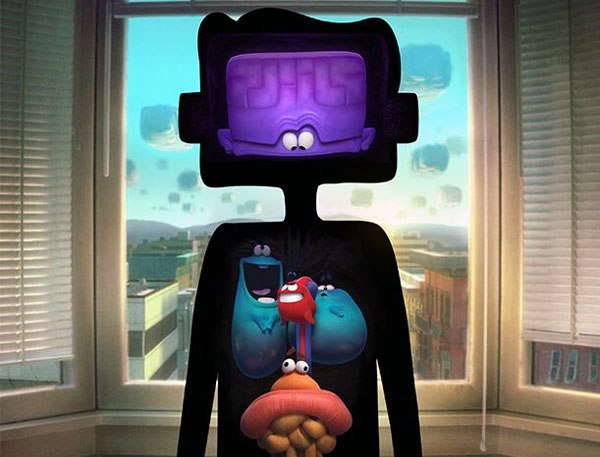

Opening Image: An instruction manual of the body opens to show the different layers of anatomy that make up the Man, an ordinary office worker.

Set-Up: The Brain wakes the Man up and sends him through his daily routine. As the Brain signals the Heart, Lungs, and Stomach to become more active, the Man gets up and begins to get ready for work. Although all organs play an important role, it is clear that the Brain is in control. However, unless the Man is able to deviate from his thesis world, it’s Stasis=Death for him.

Theme Stated: Though not explicitly stated, the theme centers on the need for balance between heart and mind.

Catalyst: As the Man listens to music during his morning shower, the Heart begins to beat to the rhythm and take control, making the Man dance.

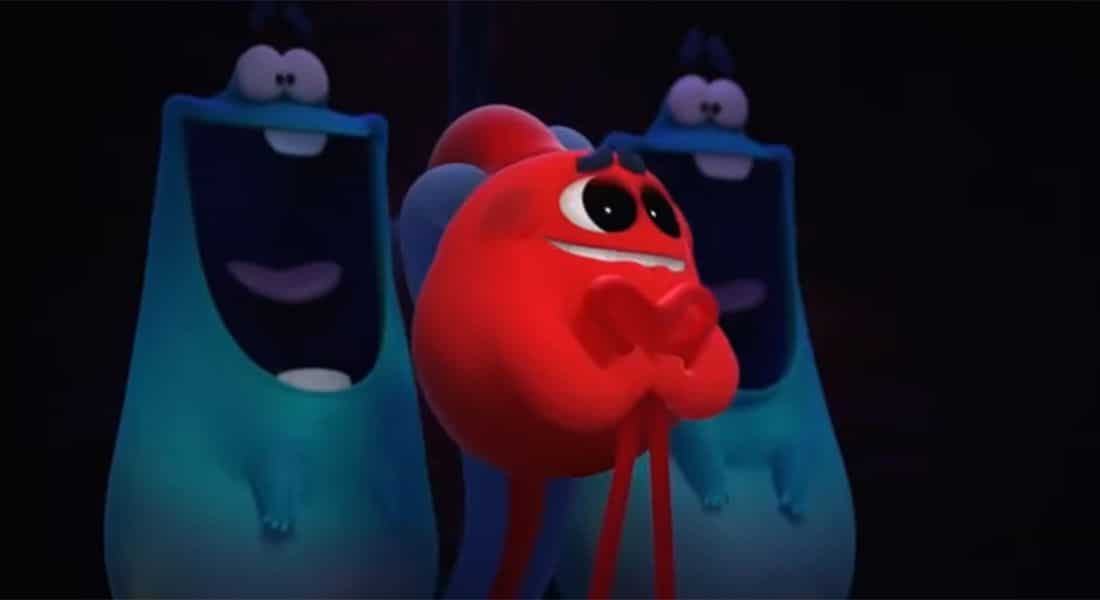

Debate: The Brain considers the ramifications of letting the Heart have some control; if the Man dances, he could slip and fall in the shower and die. Immediately, the Brain wrests control of the Man from the Heart, tugging on the Heart’s reins. It must keep the Man in sync with the daily routine.

Break into Two: The Man puts on his name badge and goes to work.

B Story: The B Story in this short revolves around the relationship between heart and mind as the two struggle for control.

Fun and Games: The promise of the premise is seen on the Man’s way to work. As he walks through town, his Heart entices him to try new and exciting experiences, the antithesis world to the Brain’s structure and routine. But whether it is eating a fattening meal, talking to a beautiful girl, or surfing in the ocean, the Brain can imagine only one ending to each scenario—death. The Brain struggles to control the impulses of the Heart and get the Man to work on time.

Midpoint: A and B Stories cross as the Brain finally succeeds in getting the Man through the door to his job, though it’s a false victory. The stakes are raised, because the Brain must maintain control, while the Heart longs for something more. The Brain takes control of the Heart’s reins, forcing it to surrender.

Bad Guys Close In: The Man sits at his tedious desk job, just one individual in a sea of many. In the bleak and dreary environment, he performs monotonous and boring tasks, his Heart sinking. The Brain notices the workers around him, and a new scenario comes to mind: one in which the Man gets older while sticking with the daily routine.

All Is Lost: In the scenario, the Brain imagines the Man’s point of death after having lived a long and safe life… but has he actually lived? The whiff of death is strong.

Dark Night of the Soul: In a brief moment of reflection, the Brain realizes that the Man needs a balance between heart and mind to be whole.

Break into Three: The Brain gives back the reins to the Heart as A and B Stories meet.

Finale: At lunch, the Man runs out into his synthesis world, engaging in all of the activities he wanted to during the Fun and Games, truly living as the Brain adapts to sharing control.

Final Image: The Man returns to his job, transformed. Instead of sitting at his desk, he dances to his own beat, the life he exudes spreading to those around him.

Cory Milles

3 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

What a great example of how a strong theme when paired with a well-built story structure combine into meaning for the audience. Beautiful!

I disagree with Blake Snyder’s contention that the theme needs to be stated early (assuming that the definition of theme is some sort of belief or tenet or assertion that the movie as a whole makes). Specifying the movie’s philosophy near the beginning eliminates the possibility that the story will head in another direction, thereby “spoiling” the film for the viewer.

The theme should be stated as one (or more) of two (or more) possibilities, i.e. there should be thematic conflict. The audience should be wondering “What if it goes in the other direction?”

In this particular case, the statement “Though not explicitly stated, the theme centers on the need for balance between heart and mind” suggests that there will be no counter-theme, and how would there be? Who would assert that there is no “need for balance between the heart and mind”?

If you watch a lot of movies, you’ll notice that the “topic” of theme will be announced early (as a general rule), but the direction that the movie ultimately heads in will not be specified; instead, there will be some sort of debate or discussion by two people whose philosophy differs.

Hi, Al. Thanks for adding to the discussion. In response to your comment, the Theme Stated beat basically sets up the thematic premise of the film, just as you mentioned. Blake wrote that the theme is usually referred to somewhere near the start of the film, but it is done so in an offhanded, conversational way. It’s a remark that the main character “doesn’t quite get,” but will be meaningful and have a huge impact later. And, as you pointed out, it is debated throughout the story. Blake also said in reference to this aspect that a good screenplay is like an argument that takes the thematic premise and examines all aspects and sides of it.

One of my favorite examples is in the movie WRECK-IT RALPH… the main character is a “bad guy” and is told, “You can’t change the program.” In other words, the thematic premise revolves around identity… are we programmed to be and act a certain way, fulfilling a certain role? Or do we have choice and free will? Another example is in SPIDER-MAN 2. Peter Parker is late to work, which impacts his employer’s promise of a 30-minute guaranteed delivery. When the owner confronts Peter, he tells Peter, “To you, a promise means nothing.” This is the thematic premise that is explored throughout the story… what does a promise mean? Is it ever okay to go back on one? How many promises can a person make or keep? Is it better to keep a promise even though it might make you unhappy to do so?

So in essence, your comments are right in line with what Blake wrote about the thematic premise. In the beat sheet above, perhaps I should have reworded the beat to reflect on how the animated short sets up the thematic premise: Is it better to live with structure, dependability, and order (and safety)? Or is it okay to follow your heart even though it involves risk? Does there need to be a balance of both?

Thanks for bringing up the topic for discussion. I’d love to read other examples of how a thematic premise is done well in a movie!