For any movie lover, lover of film history, and especially lover of Citizen Kane, the pleasures of Mank are many. It is a backstage showbiz tragicomedy focusing on the struggle of screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Mank) to write his most important work, the screenplay to Citizen Kane, drawing on his deep knowledge of the source material: his personal relationship with media magnate William Randolph Hearst and Hearst’s mistress, movie star Marion Davies.

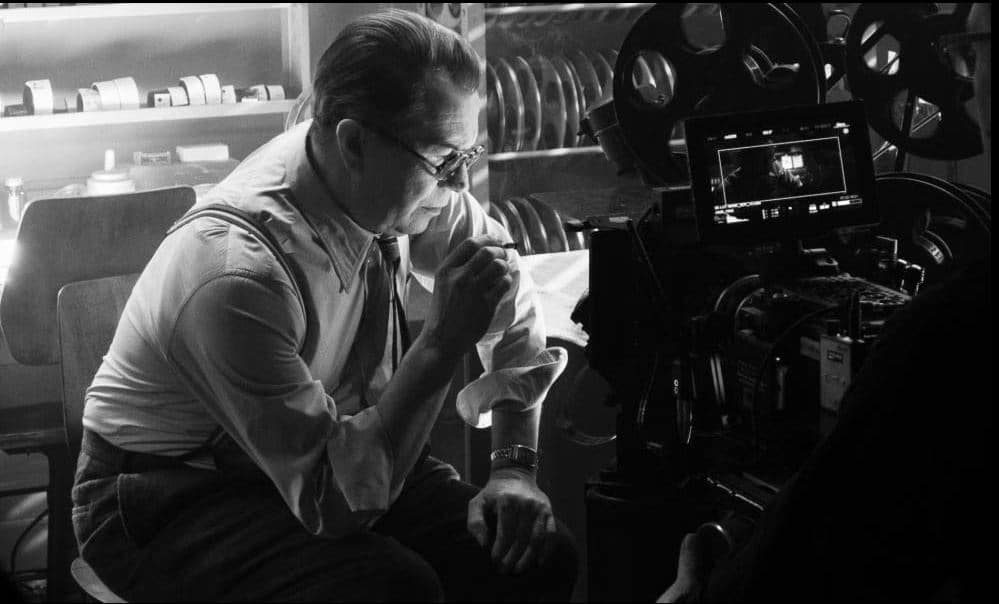

Mank is the origin story of Kane told much in the style of Kane, and this is the Fun & Games at the center of the film: how to pay loving homage to a film classic in as many ways imaginable, from the stunning black & white cinematography, camera staging and transitions, musical references, moods, story structure, and the very act of transforming Hollywood history into narrative fiction. These echoes and parallels between films is ever-present and served up in a non-stop parade of cinematic Easter eggs and offhand allusions that cinephiles will find delicious, executed with the astonishing degree of technical meticulousness that has come to be expected from a film directed by David Fincher.

Fincher is not just paying homage to Kane but also to an entire era of film history, the “Golden Age of the Studio System” from 1930 to 1942, the context in which the film is set. As Fincher has said, he was making a film as if it had been waiting “in Martin Scorsese’s basement on its way to restoration”—that is, a film that feels as if it had been made then, not now. It is purposefully and ingeniously anachronistic.

And much like two films I have written about before on this website, La La Land and Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, Mank is part of a wonderful tradition of movies about making movies, and one that should be particularly meaningful to the Save the Cat!® readership since it’s about a screenwriter and presents storytelling as a heroic act of memory and imagination fueled by intelligence, nerve, perhaps a bit of revenge, and of course, “support devices.”

It is also one of the purest examples of the Fool Triumphant genre in recent memory. It is so apparent that it seems improbable that the filmmakers were not conscious of this, though it may be that they understood it without naming it as such. Still, Fincher (like Damien Chazelle and Quentin Tarantino) is a learned connoisseur of film history and narrative mechanics and this film is just as self-aware as those named above—and similarly thoughtful and playful.

Indeed, I consider it the most playful, and the warmest, of any Fincher film. This is largely due to the enormously entertaining Fool at its center, played by cinematic treasure Gary Oldman, who plumbs Mank’s wit and humanity with depth and invention, but it is also due to the palpable love the filmmaking team has for its subject, and the rich tapestry of Fun & Games in a story by, for and about lovers of film.

Fair warning, SPOILERS AHEAD!

Blake Snyder identified three aspects to the Fool Triumphant genre: 1) a Fool whose innocence is his strength and whose gentle manner makes him likely to be ignored by all but the jealous Insider who knows too well; 2) an Establishment, the people or group a fool comes up against, either within his midst, or after being sent to a new place in which he does not fit – at first; and 3) a Transmutation wherein the fool becomes someone or something new, often including a “name change” that’s taken on either by accident or as a disguise.

Mank is a fool on many levels. He is a wit, he is a drunk, and he is a screenwriter(!). In Hollywood, even a successful screenwriter like Mank is relatively low in status, which is what makes him ignorable. Still, Mank’s position in the hierarchy is fluid as the head Fool in “a fool’s paradise”—running a Hollywood writers’ room at Paramount between stints at MGM, having earned his position by being the cleverest guy in the room, the observer who misses nothing, and possessing a moral decency and conviction essential for the armchair provocateur. He is both “top dog” and “underdog,” which suits him well.

He is a former member of the infamous Algonquin Round Table of New York intellectuals, and so he is appropriately erudite, sophisticated, and never without an astute comeback even when perilously drunk, which is often. Mank’s alcoholism is his Achilles Heel but also a source of strength that untethers his wisdom and wordplay from self-censorship, and this is a kind of “innocence” that works to his advantage until it backfires spectacularly. It is also a source of humor and pathos from this “lovable drunk.”

Though Mank has his own ethical code, he is also a player who games the system at every turn, and when asked if he is ever serious about anything, his self-knowing response is spot-on: “Only about something funny.” He is the ideal “court jester,” a term used to describe him by enemies and allies alike, the role he occupies more or less officially after fortuitously impressing William Randolph Hearst with his repartee enough to be invited into the inner circle of San Simeon.

There he takes a seat at the banquet alongside the studio chieftains and A-Listers, presided over by the king of this castle and the real power in this world, Willie (W.R.) Hearst. I can’t think of a better character than Mank to wear the hat of Hollywood Fool—an unintentional and careless master of ceremonies that allows us a privileged glimpse inside the highest (and lowest) echelons of Tinseltown power.

Tinseltown is precisely the Establishment (the Showbiz Institution) in which our Fool operates and is “the group he comes up against” in two primary timelines: 1) “the present” (1940) depicting Mank’s struggle to write the script for Kane under deadline pressure, and 2) “the past” (1930-1940) told in multiple flashbacks depicting Mank’s rise and fall as a studio writer and court jester, experiences that inform the creation of the script.

Another aspect Blake attributes to the FT genre is the Dual Arena, and though the two contrasting timelines can be thought of as one kind of Dual Arena, each timeline actually has its own: the present shows Mank prior to his auto accident, unemployed and in need of a job, and afterwards when he’s bedridden (Transumuted) and convalescing in Victorville, CA, having been hired by Orson Welles and RKO Studios to write the script for what will become Kane. The Dual Arena in the past toggles between Mank’s life at the studios and the rarefied air of Hearst Castle, and the Transmutation from contract writer to court jester among the elite.

The multiple flashback structure is another tip of the hat to Kane, the primary Fun & Games in the film as a whole, but it’s also within the Showbiz Institution where another kind of Fun & Games is at work, the F&G of inside Hollywood jokes as the film deftly satirizes prevailing attitudes regarding the status of writers, directors, and producers (still held today), dismissing writers as inconsequential (Thalberg’s remark to Mayer’s question, “Who was that again?” “Just a writer.”), showing the lure to direct as an irresistible and corrupting siren’s call (the Shelly Metcalf faux documentary propaganda subplot), and the role of the producer as something requiring no talent (Mank to Shelly, referring to Shelly’s worsening Parkinson’s Disease: “You can always produce.”), and, of course, the shifting sands of one’s position and reputation (Mank to David O. Selznick after his prestige has slid: “I couldn’t get past your secretary’s secretary.”).

This brand of Fun & Games—and the point of view of the entire film—gleefully mirrors the attitude held by Mank himself: that of the cynical and knowing insider treating the studio system as a three-ring circus ripe for satire, simply fodder for the Algonquin wit who benefits from studio largesse even as he ridicules it. The way the film captures the aloof intelligence and incessantly genial snark that Mank typifies is one of its greatest satisfactions, courtesy of the impeccable script by Jack Fincher and the director’s attunement to its sensibility. It’s completely understandable that screenwriter and director are real life father and son and that this film gestated for decades. It’s also understandable that Jack Fincher was a newspaperman who was writing about a newspaperman who wrote about a newspaperman: “Write what you know!”

What elevates the film beyond satirical romp is showing how this Institution is far more complex than a circus tent providing mass entertainment. It is part of a broader and much more nefarious context of political realities focused on money, power, influence, ruthless self-interest, and self-perpetuation. This is presented through Mank’s political awakening in the flashbacks involving the California Governor’s race of 1934.

Adding complexity (and culpability) to these events is shown by Mank actually providing the ultimate Insider Thalberg (and in turn, Hearst) the idea to use studio resources to make fake newsreels to discredit Upton Sinclair, the candidate that threatens studio interests and Big Money—though Mank is clearly aligned with Sinclair’s politics (and in the moment fails to recognize that he imparts a winning strategy that will be shrewdly exploited by Thalberg).

Much to Mank’s dismay, this strategy works. Sinclair loses, and Mank’s friend, Shelly Metcalf, another committed liberal, kills himself over his role in directing the fake newsreels. This is a double-black moment for Mank, a Dark Night of the Soul that motivates his climactic speech at Hearst Castle: all that a good court jester can do to express his outrage is speak truth to power, and Mank does what he does best in spectacular fashion—fearlessly confronting the Establishment through inspired (and drunken) yarn-spinning.

Though this results in his ignominious exile, he now has the rough outline for what will become Kane. This is a brand of Fun & Games, too—the F&G of emotional complexity and irony. And by the way, the political awakening subplot is a timeless comment on mass media manipulation and the weaponizing of “infotainment” for political ends, which is exactly the intention of all propaganda then and now.

The process of writing Kane is another act of speaking truth-to-power, so Mank still wears the jester hat in “the present” while he’s pursuing his goal of completing the script, and still fearlessly comes up against the Establishment as the parade of allies visit him to impart dire warnings about the cost of truth. Despite this, Mank perseveres; he is, above all, a writer with a story to tell and a deep need to tell it, in addition to being comfortable with flouting the rules, even if it’s a path to self-destruction (which it is and it isn’t).

Another layer of the Fool Triumphant genre is the use of Don Quixote as a reference used explicitly in Mank. Don Quixote is perhaps the first Fool Triumphant in Western Literature, and informs all others: the Alpha-FT. Mank, who knows his literature backwards and forwards, tells Marion Davies that he thinks of her as Dulcinea (the love interest in DQ), and later, in his tour de force “pitch” to the assembled court at San Simeon, he frames his story as a “modern day Don Quixote” where the character based on Hearst is the newspaperman with ideals “tilting at windmills.”

In this pitch he makes an interesting parallel between Hearst and a character based on Sinclair, who he at first presents as the nemesis of the story, but at the end reverses their roles and presents him as the hero to Hearst’s “fallen” Don Quixote. This is essentially what Mank does with his script to Kane, where he depicts Charles Foster Kane as an idealistic young man who betrays his ideals as he’s inexorably corrupted by his ambition and ego and winds up despised and dying alone. Don Quixote is a metaphor for staying true to one’s liberal and humanist ideals, so Mank himself is a Don Quixote figure tilting at windmills in his role as writer and truth-teller.

By extension, Welles is also a DQ figure as he ultimately brings Kane to fruition and reaps the rewards and also suffers the consequences. And of course Hearst is the once idealistic nobleman who betrays his ideals in his pursuit of power and self-gratification. All three principal male characters in Mank are united by the Fool Triumphant metaphor.

Among these three, only Mank is the “organ grinder’s monkey,” another explicit metaphor used in the film, a fable imparted to Mank by Hearst as he’s walking our Fool out San Simeon’s front door for the very last time. The Monkey in the tale deludes himself that he is in control of the organ grinder, when the exact opposite is true. Surely a foolish belief held by “Monkey-witz,” as L.B. Mayer had called him just minutes before.

“Nobody makes a monkey out of William Randolph Hearst!” screams Marion on a nighttime stroll with Mank through San Simeon’s private zoo, a portentous foreshadowing. And yet Mank can do nothing less than “sticking the old neck out.”

If Mank is a Fool Triumphant story, what is Kane, the masterpiece that Mank wrote? In reflecting on both films, I happened to rediscover an essential bit of story wisdom from Blake Snyder. In Save the Cat!® Goes to the Movies, Blake shares this noteworthy insight: “The Supherhero genre is most like the Fool Triumphant; there is a lot of crossover when dealing with stories of being special.”

That made me consider Kane in a new light. The film is renowned for its groundbreaking narrative structure of overlapping flashbacks told by biased narrators, but its genre is slippery. Blake identified it as a Whydunit. I agree with that as far as the framing story goes, which follows the journalist Thompson searching for the meaning of the word “Rosebud” and serves as the thread which connects the stories-within-stories told by 1) Thatcher, 2) Bernstein, 3) Leland, and 4) Susan Alexander. But do these individual stories have their own genres (I think they do), and is there an overarching genre that unites them all? I propose that there is: the Superhero genre. Bear with me.

That genre consists of three parts: 1) the hero must have a Special Power, even if it’s just a mission to be great or do good; 2) the hero must be opposed by a Nemesis of equal or greater force, who is the “self-made” version of the hero; and 3) there must be a Curse for the hero that he either surmounts or succumbs to as the price for who he is.

Kane’s “superpower” is his supreme wealth. It separates him from his peers as completely as if he had been born on Krypton. His inheritance makes him a King of Capitalism (a “Capitalist Superhero”) completely untethered by society’s rules. This fits him like a comic book gauntlet, since he is also a rebel who prefers breaking rules to following them (sound familiar?).

Furthermore, he possesses another Special Power, a calling to both “be great and do good.” This is illustrated in the scene where he devises the “Declaration of Principles” for his newspaper, witnessed by his best friend and chief ally Leland and Mascot Bernstein. He sets out to be the champion of the common man and his paper will be devoted to the interests of that readership, simply because he’s a “man of means” willing to do it. Like young Hearst, the young Kane has ambition and ideals.

Kane also has a Nemesis. Actually, he has several: anyone who opposes his indomitable will (which is another Special Power). In the Thatcher flashback, it’s Thatcher; in the Bernstein flashback, it’s the newspaper editor Kane inherits and his rivals in the newspaper world; in the Leland flashback, it’s Boss Jim Gettys (the self-made political rival) and after that, Leland himself; in Susan’s flashback it’s Susan. Yet none of them are his equals. They are mere mortals pulled into his orbit by the gravity of his wealth and personal force.

In a standard Superhero story the usual approach is to compare and contrast the Superhero with a single Nemesis, or the last in a string of oppositional characters that is revealed to be orchestrating all who came before. This emphasizes the power of the Nemesis and increases the magnitude of victory when the Superhero ultimately triumphs. But Kane is not standard, nor is it about the sweet victory of vanquishing an opponent. Kane is about loss; it is the story of an exceptionally privileged man who “succumbs” to his character flaws. Kane himself inadvertently (but inevitably) orchestrates his own downfall.

That brings us to the Curse which, to me, is the entire point of Citizen Kane. It is why it is such a remarkable characterization and enduring film—the Curse is the tragedy of Kane, the very thing that explains his own self-assessment that “If I hadn’t been born rich, I might have been a really great man.”

The answer, of course, is Rosebud, or what Rosebud signifies: the primal psychic wound from which the boy Kane would never recover, having been torn from his parents (especially his mother—and yet, it is orchestrated by her!), his home, and all that he knew when he was at his most vulnerable and sent into the exile of wealth and privilege. These events instill in young Kane a hunger that can never be satisfied. It also hardens him like steel.

ironically cast into the incinerator, undiscovered by all but the audience

Rosebud explains why Kane’s inheritance is a winning lottery ticket that “curses” his life. What energizes this revelation with potency and irony is that it is withheld from the journalists in the framing story who are desperately seeking it and are in the end forced to abandon their search, concluding that if Rosebud exists at all, it likely means nothing. But, of course, it means everything. As often happens in Whydunits, we, the audience, experience this cathartic Transformational revelation, not them—and that is the pulsing heart of Kane‘s power and its profound sadness, and it results directly from this Curse that is conceived of and presented with such brilliant narrative artistry by Herman J. Mankiewicz, the Fool who chronicled a King.

Mank and Kane—even their genres perfectly reflect each other; opposite facing its reverse, self-sabotaging Joker and Suicide King.

It is arguably Mank’s greatest achievement as a storyteller that he makes such a deeply unsympathetic man (Hearst/Kane) wholly sympathetic, and makes the moving target of his personality fundamentally understood at the end. Much credit certainly must go to Welles for his towering performance of Kane that radiates with charisma, vitality, and authority (that man could play kings!), not to mention his masterful and magnificently original direction (and, “cough, cough,” contributions to the script!).

But it all starts with the blank page, and Mank elevated a “notably rich and powerful,” muckraking media baron to the level of tragic hero. The organ grinder’s monkey has the last laugh in real life as the cultural legacy of the film he authored echoes across the decades and American culture with greater resonance than most of what Hearst accomplished, deeds tied to his historical moment and largely forgotten (a debate about the toxic tradition of yellow journalism is for another day).

Great art, on the other hand, transcends such ties, which is why Kane lives today, still considered among the greatest films ever made. And though Mank’s (and Welles’s) rendering of Hearst/Kane is perhaps more than Hearst deserved, Mank knew otherwise; everyone is a hero in his and her own way, even anti-heroes and villains. In fact, Mank could do nothing less, because he knew that humanizing Kane was the best version of the story. And the echoes between films reverberate again as we learn, at the end of Mank, that our hero reclaims his once renounced writing credit and wins the Oscar® but is undone by his addictions, and his finest professional moment is the end of his career. The Fool Triumphs, but like Kane, he succumbs to his character flaws. Fate can be heartbreaking, which is the takeaway of much of the greatest and most powerful art.

I consider Mank a perfect funhouse mirror counterpart to Kane, made with all the intelligence, artfulness, craft, chutzpah, and literary ambition as that to which it pays homage, while also revealing the essential contribution to a lasting work of art by a man that history has, until now, shortchanged. The film is nominated for 10 Academy Awards. That’s one more than Kane itself received.

And though Kane only won one award—the Oscar for Best Screenwriting—the screenwriter for Mank, Jack Fincher, was shut-out from a nomination. I guess an exceptionally award-worthy film just writes itself(!), and the writer’s status has taken a step backwards in the intervening years. Irony prevails, alas. And I guess that’s fitting, too, in a “Mankian” sort of way.

Again we can see the genius behind Blake Snyder’s tools for examining the underlying mechanics of storytelling, in particular his truly original system of genre classification. It is a profoundly useful tool in guiding one’s story choices and helping to understand the choices made by other storytellers. Thank you, Blake!

And while I’m thanking people, allow me to extend special thanks to Team Fincher and all of the artist-filmmakers (special shout-out to Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross for their remarkable score) for letting me live in Mank’s worn-out shoes, booze-soaked suit, and crumpled hat on his wisecracking fool’s journey through the sun-baked and shadow-drenched heart of Hollywood in its heyday.

And thanks to Mank. And Welles. Thank you all for your exceptional “Genius at Play!”