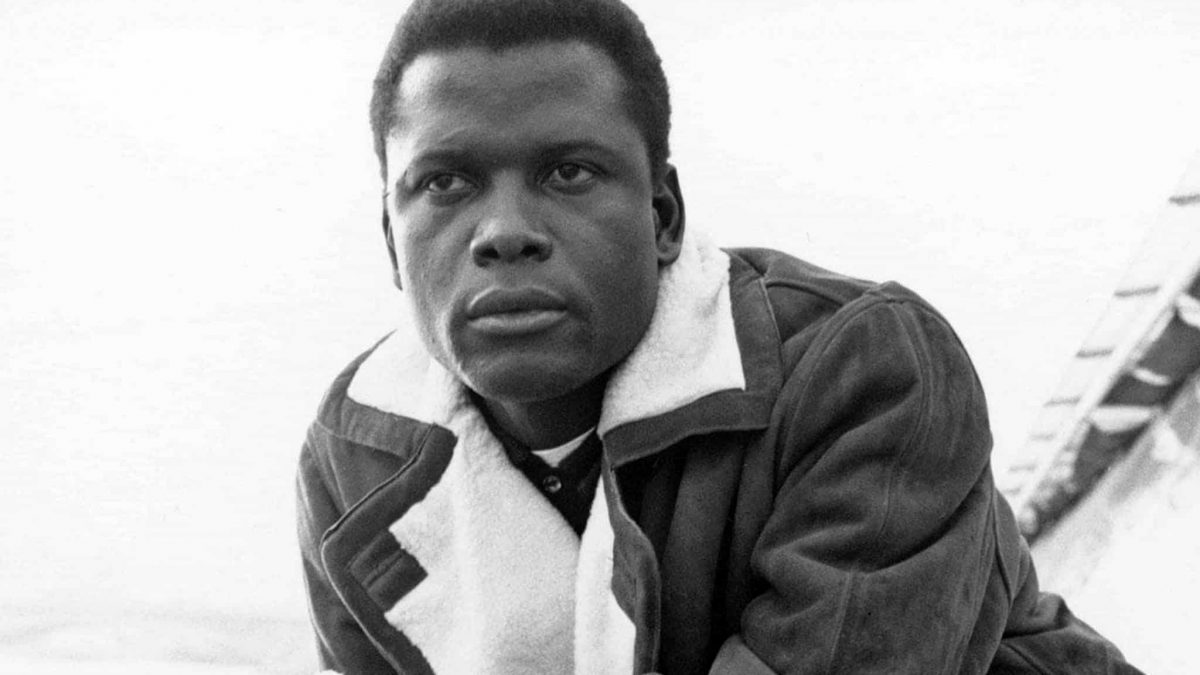

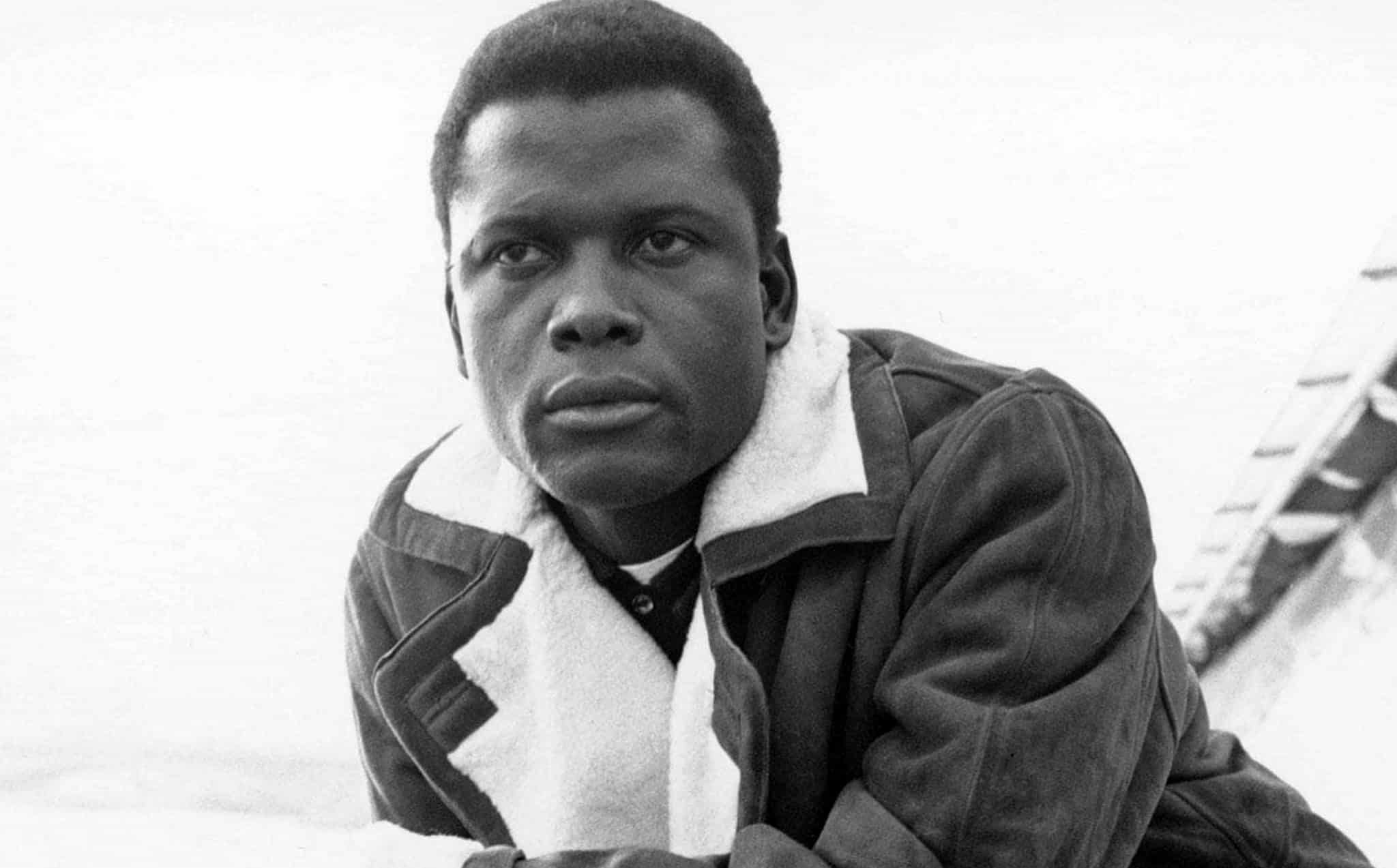

Sidney Poitier was born in the winter of 1927—somewhere in Dade County, Florida.

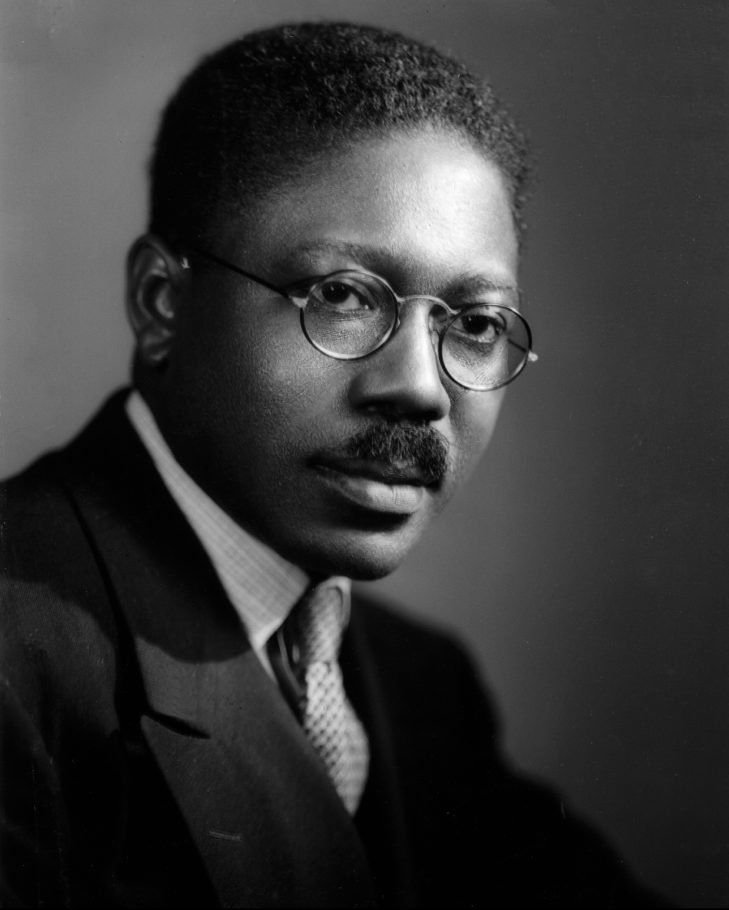

Aaron Douglas was born in spring of 1899—somewhere in Shawnee County, Kansas.

But it was in New York City that both men found their way. Perhaps they casually stood side-by-side having coffee at an Manhattan automat or were in the same car on the A Train—we don’t know. What we do know is they inhabited the same spiritual space, creating works of art and film relevant to the challenges of their time—and our time.

THE CONNECTION

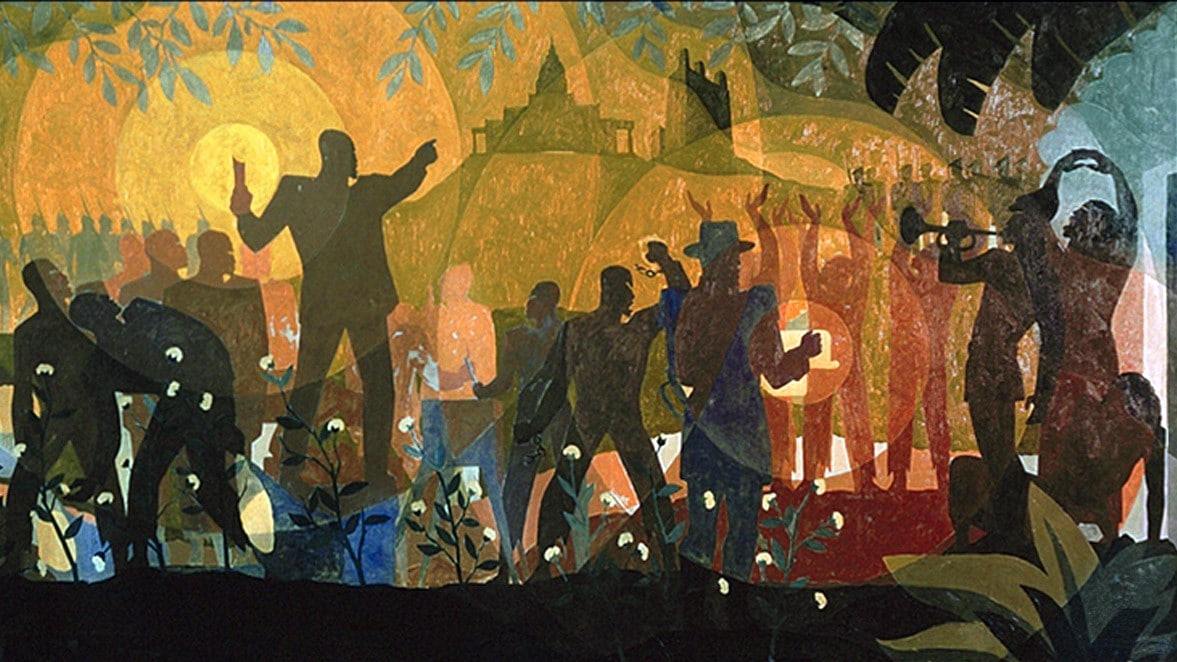

There was an exhibit building at the 1936 event—The Hall of Negro Life and Culture—which skillfully presented the sojourn of Black folks on American soil. Douglas’ murals were the centerpiece of this exhibit, defining and infusing it with a controlled power and pathos. His work embodied a revolutionary ideal.

I’m in the final, frenzied weeks of post-production on a film about the Texas Centennial Exposition and World’s Fair of 1936 that’s going to air during Black History Month. While editing a sequence on Douglas, I learned that Poitier had died. Until that moment, I’d never connected the two men. Poitier’s acting evinced a controlled power and pathos, similar to Douglas’ murals.

Douglas became the preeminent muralist and visual impresario of the Harlem Renaissance. His illustrations wrecked prevailing myths about who and what Black people were—and could be. The Texas murals troubled whites so much that one woman boldly asked: “What ‘Negro’ did this? I don’t think it’s possible that any Negro could have made these murals.”

Although Poitier and Douglas were about 30 years apart in age, they shared a certain kind of artistic essence and zeitgeist that is more than anecdotal.

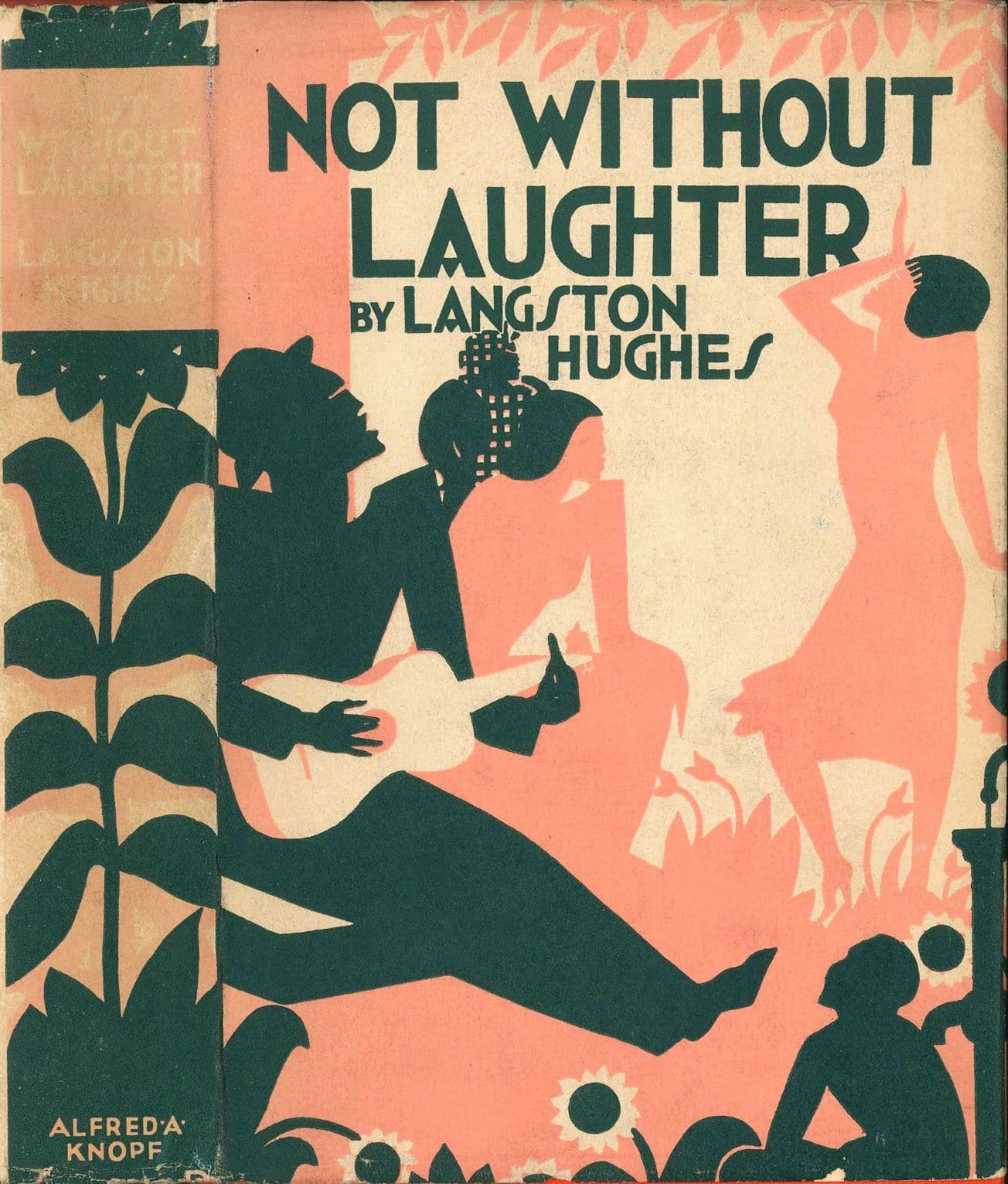

Douglas’ illustrations for the novels of James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes, or his illustrations for Crisis magazine, shaped a different lens to view Black men. Poitier’s “sizzling seven” body of work—No Way Out, The Defiant Ones, A Raisin in the Sun, Lilies of the Field, A Patch of Blue, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and In the Heat of the Night—further shoved a different image of Black folk into the peripatetic middle American viewers of Hollywood movies.

When we weren’t shown picking cotton, singing, shuffling, or sleeping on the porch, we were presented as the quintessential coward, so terrified of our shadow that we quaked at the voice of any white person. This image of the cowardly—though 180 degrees from the truth—received an imprimatur from the land below Los Feliz, while elevating them to the U.S. pantheon we know as “Hollywood History.”

Poitier altered that. I watched the powerful No Way Out (with Richard Widmark, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz) where Poitier plays Luther Brooks, MD. (Wait, a black man is playing the doctor, not the shuffling orderly balancing bedpans and brooms… what’s wrong?) This was 1950.

Eight years later, in The Defiant Ones, Poitier plays a character, Noah Cullen, who escapes from a prison work gang chained to Tony Curtis. It’s entertaining and watchable. The Defiant Ones evinced a kind of metaphorical cloud cover where the cultural message reflected brighter than the picture. Despite how we feel about each other—or don’t feel about each other—United States history has soldered the destinies of Black and white folk into a single forged piece of metal. To quote the lyrics of Chuck Jackson and Marvin Yancy, as immortalized by Natalie Cole: “…inseparable, that’s how we’ll always be.”

Poitier’s Homer Smith in Lilies of the Field—for which he won an Academy Award®—was released in the fall of 1963, less than 80 days from when the great Medgar Wiley Evers was assassinated in the driveway of his Jackson, Mississippi home. Evers’ wife and children were inside and heard the blast. The character Smith was a veteran. And so was Evers. Could Poitier have invoked the memory of Medgar Evers on Oscar night? I don’t know. I wish that he would have done so. But those were different times, I guess.

Poitier was excoriated in a 1967 New York Times essay by Clifford Mason which argued that his movies were a “flight from historical truth” and that he was a “pawn for the white man’s sense of what was wrong with the world.” Another national publication wrote that Poitier accepted a role that would allow him to be the white man’s “good Negro.”

I am drawn to Sidney’s early life, as it represented the kind of corrosive struggles endured by the poor. His family were from Cat Island in the Bahamas, but his Mom—while working in Miami—went into labor three months before her due date (as the story goes).

And, it’s a good news/bad news paradigm: Another pre-term birth of a black child [bad], but Miami gave Sidney an opportunity to return to the U.S [good]. At 14, he returned to the U.S. to live with a relative, which led to an encounter with four white men who wanted to “teach him a lesson” because he had frightened a white woman while delivering a package to her door. (His job was to deliver packages [bad].)

Poitier escapes to New York, where he worked as a dishwasher, a waterfront laborer at the Port Authority, a lookout man for craps games, and a janitor [good]. He lived a mostly shelter-less existence for seven years, sleeping in buildings or pay toilets while learning his craft at the American Negro Theatre on 135th Street—not too far from where Douglas was painting the murals that re-calibrated the African-American narrative.

Douglas, too, a quarter of a century earlier, felt the call of New York City. He arrived from Kansas City with no friends, no family, and no money. He was nearly destitute, but held a massive dream that called from the future. I wonder if Douglas passed Poitier on the street some evening. Did Poitier ever sleep in the YMCA that housed Douglas’ murals? These are questions I long to have answered.

THE SLAP

Few movie scenes re-orient the viewer like Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs’ slapping of cotton magnate Endicott in the greenhouse following a soliloquy about how the “fragile southern Negro had to be protected like an orchid” in In the Heat of the Night. I wonder how that scene played in Peoria—or, for that matter, Pensacola.

With the slap, Detective Virgil Tibbs (like Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore describing “napalm in the morning” in Apocalypse Now) was propelled onto the movie Mount Olympus—at least for black folks. Every black person felt the archetype of Endicott’s character—we had seen him in the face of department store clerks and peace officers and school counselors and the smattering of condescending looks when we stepped onto elevators.

In the scene, Endicott touches his swelling face and says, “… there was a time when I could have had you… shot.” We cut to Poitier’s reaction, followed by inserts of the impeccable Rod Steiger as Sheriff Gillespie, then back to Endicott. Poitier exits the greenhouse, saying nothing. We cut to Henry (Endicott’s black servant) as he either agrees or disagrees at the insolence of an “uppity Negro” who, at a different time, could indeed have been shot. The exchange between Henry and Endicott is subtle, but poignant.

Aaron Douglas delivered a certain kind of slap with the four murals he painted for the 1936 Texas Centennial. For an event created as an homage to the accomplishments of Anglo-Saxon history and culture—and the intentional re-framing of aspects of history to fit a new, more palatable narrative—Douglas, on 6 x 6 panels, gave Texans the truth of the journey of African-Americans… as told by African-Americans. He lifted the viewer from the proscenium of mediocrity that then infused images of us to a kind of bold and brash confidence that made not a few uncomfortable.

I believe both Douglas and Poitier despised the resonating smallness that infused images of how Blacks were portrayed. When others told our stories, there was rarely an opportunity do anything more than to be presented as the least. If you needed an image where someone was afraid, make it a black person…if you needed a bumbling coward, make that an image a black person… if you needed a servant or a brute, a pimp or a sad face to dump the slop jars, cast a black person. We were simultaneously boxed and “boxed-in” by this imagery.

To borrow from Cole Porter, the images sang the damn refrain: “….this is your history, your destiny, your reason to be, and the punishment for setting your people free…” These were the images—in print and on film—that Poitier and Douglas endeavored to smash while constructing a counter-narrative. The two men believed that images of Black folks should not be defined by the “least of us” but the “truth of us.” For those who choose not to see, truth is an unwelcome visitor.