Thanks to Cats! Jennifer Chang and Jose Silerio for their beat sheet of the 1960 Oscar®-winning script (Best Writing, Story and Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen) from Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond. The Apartment won 5 Academy Awards®, including Best Picture and Best Director for Wilder.

And speaking of winning, congratulations to the winner of The Apartment Beat Sheet Contest (sorry for the delay in announcing this): Sue Kylen Berg, a Seattle screenwriter who is a graduate of the University of Washington Extension Screenwriting Program in 1997 and Blake Snyder’s Seattle Beat Sheet workshop in July 2008. Great work, Sue!

We hope our fellow Cats! can appreciate how this beloved piece of cinema, which predates Save the Cat! by 45 years, hits Blake’s 15 beats so cleanly. We can’t say it enough: good story structure is timeless!

THE APARTMENT BEAT SHEET

1. Opening Image: C.C. Baxter sits in an office where he’s clearly a cog in a machine. He works overtime to avoid the foot traffic, but also to avoid interrupting the activities of executives to whom he’s lent out his apartment for illicit rendezvous.

2. Theme Stated: When an executive, who regularly uses Baxter’s apartment, is asked who owns the apartment, he merely replies, “What’s the difference? Some schnook that works in the office.”

3. Set-Up: Baxter’s execs set him up for a promotion with hopes that he won’t let them down. Even when he’s in bed already, Baxter still gives up his apartment when another executive calls him late at night to bring a girl.

4. Catalyst: Baxter goes to Sheldrake’s office and is confronted with the nature of his dealings with the other execs. Sheldrake wants in.

5. Debate: Baxter goes along with Sheldrake’s request in return for the promotion he’s been coveting.

6. Break into Two: With his new confidence, Baxter asks Fran Kubelik, the elevator girl, out on a date, but she says she has an engagement right before.

7. B Story: Fran and Sheldrake have a meeting and discuss their past fling, and his intention to resume it. Baxter is ditched at the play while Fran and Sheldrake visit his apartment, as scheduled.

8. Fun and Games: Baxter gets his promotion to Junior Executive and is given his own office. Meanwhile, the other execs aren’t happy that Baxter has stopped sharing his apartment with them. Baxter makes a bigger, more confident play for Fran, trying to impress her with his new junior executive status. All the while, Sheldrake is telling him about his latest fling. Baxter is oblivious that it’s with Fran.

9. Midpoint: Fran grows wise to Sheldrake’s philandering at the office Xmas party. Baxter discovers by way of a broken mirror she left at his apartment that Fran is Sheldrake’s mistress.

10. Bad Guys Close In: Sheldrake takes Fran to Baxter’s apartment on Christmas eve. When Fran realizes how little she matters to Sheldrake, she overdoses on pills there. Baxter brings a random girl home, drunk, and finds Fran passed out. He employs the help of the next-door doctor to bring her to. Baxter promises to help Sheldrake handle the situation with Fran while he keeps up appearances with his family. He keeps an eye on Fran for the next 48 hours. He plays gin rummy with her and listens to her while she recounts her pathetic history with men, and admits to still loving Sheldrake. Nonetheless, Baxter takes care of her, making sure she’s fine as he entertains her with his own stories and quirkiness. The other execs give up Baxter’s whereabouts to Fran’s brother-in-law, Matushka, when he comes to the office looking for her.

11. All Is Lost: In an altercation with Matushka, Baxter takes the blame for Fran’s suicide attempt to protect the secret of her affair, and he’s punched for it. The brother-in-law takes Fran away.

12. Dark Night of the Soul: But before Fran leaves, she thanks Baxter with a kiss. It’s the wake-up call he needs to realize he’s madly in love with her.

13. Break into Three: Baxter makes plans to tell Sheldrake that he’s in love with Fran and can take her off his hands.

14. Finale: He finds that Sheldrake has been kicked out by his wife, and plans to continue with Fran. Sheldrake gives Baxter a promotion. Later, however, when Sheldrake asks to use his apartment for Fran, Baxter refuses, and quits on New Years’ Eve. When Fran learns about this on a date with Sheldrake, she realizes she’s in love with Baxter. She leaves Sheldrake at the party and runs to Baxter’s apartment.

15. Final Image: Baxter tells Fran he loves her. They play gin rummy. He is no longer alone in his apartment.

BJ Markel

13 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

And again no genre or subgenre!

Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarrrrrrrrrrgfhhhhhhhhhhhghhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!!!!

That’s the way it ends… storywise.

I thought STC didn’t make sense.

Now I think it’s plain stupid.

I hope I’m wrong. But I know I am not.

Hey, SM! This is worth talking about. Please be more specific about what doesn’t make sense to you.

While I have quite lot of time for STC in general, this “beat sheet” really doesn’t do The Apartment justice. Wilder and Diamond embed in the deep structure of their screenplay in not just the basic plot elements but the subtleties and grace notes. What makes the climax work is not that Baxter determines to square up to Sheldrake, quits, and then Fran rushes into his arms. It’s the “gunshot” and the killer line “shut up and deal” (which almost reduces me to tears every single time).

Look at what has to be set up to make that “gunshot” work.

– Baxter’s earlier suicide attempt (while maintaining a light comedy-drama tone)

– The presence of the gun in the apartment

– The paper-thin walls

– Baxter moving out

– The presence of a champagne bottle

Not one of these is present in the outline above which is also frequently lacking in basic storytelling cause-and-effect.

And that’s before we get to the dual symbolism and misdirection of the key in the “Baxter quits” scene. One of the most graceful, funny and moving screenplays in Hollywood history is presented here as clunky and awkward.

What was the point of this exercise exactly?

The way I understand it, the 15 beats provide a “foundation and ironwork” for a screenplay, and it’s WITHIN that structure that a screenwriter is allowed to be free, creative, and to sprinkle in all the poignant and personal touches that make his or her story stand out as a masterpiece. The two items that the commentor points out here — though memorable — aren’t actually integral to the beats, though they do contribute to the greatness of the film.

The last beat is that Baxter is not alone in his apartment, and that they have fallen in love. Ms. Kubelik could have said ANYTHING, and that beat would have remained the same. Instead of “shut up and deal,” she could have said, “by the way, I like my eggs scrambled in the morning,” (of course, she wouldn’t have said that) and the beat would have still been the same: Baxter is no longer alone; they’re in love. Same goes for the gunshot. It’s a great moment and it really ramps up the tension in that instant before she enters the apartment. But it doesn’t change the story beat.

I think the basic distinction that needs to be drawn is the difference between a Beat Sheet and what one would consider a traditional “synopsis” of a film. A Beat Sheet outlines the skeleton upon which the rest of the movie is built. Everything else (key symbols, memorable lines, etc.) though worthy of mention in what would be a good *synopsis* that conveys why a film is special… is meat.

While those moments are part of the story and important elements in the telling of the story, they won’t be written in a beat sheet because a beat sheet talks about the overall story and not the little moments that make the movie or script more emotional. Those come with dialogue and actual scenes. For lack of a better analogy, the BS2 is the skeleton and those moments that CC Baxter talks about are the muscles and organs that make the skeleton stand better. Also, how we react to a movie is very subjective. We can agree that a movie is great or terrible, but as to what exactly makes the movie great or terrible, we’ll have different takes on it.

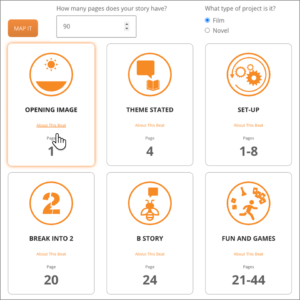

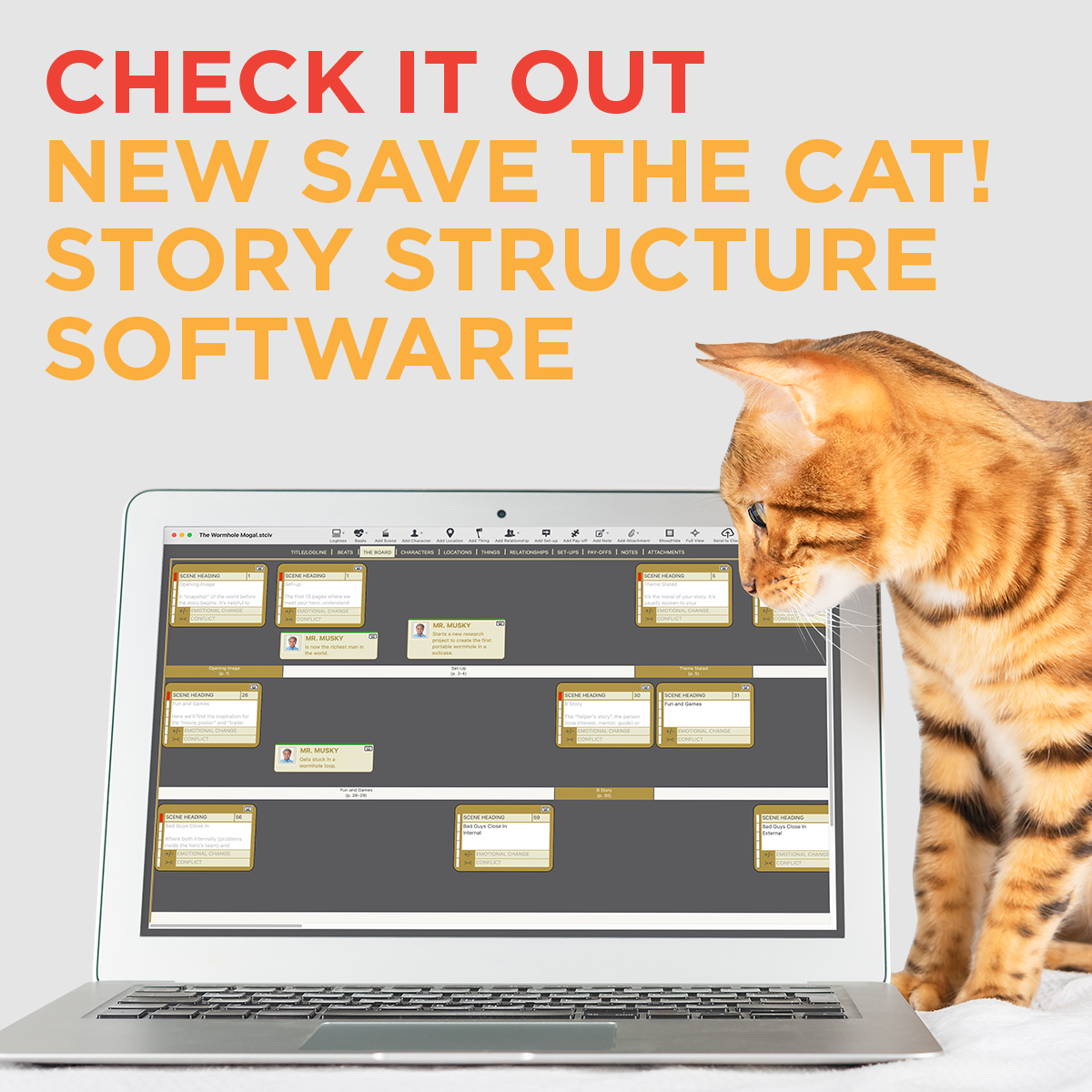

In truth, a beat sheet is a tool that helps move the writer forward. It isn’t a “backward” tool, meaning it will always be a little off to fit a movie into a BS2. Why? Because the BS2 is limited in terms of being emotional, what can be included, and how in depth it can truly get. It’s more A story than B story. That’s why Blake had one beat just to say B Story, but in the Board he goes A Story and B Story alternatingly. But this doesn’t mean we can’t learn from breaking down movies into their core beats.

Stories always change and grow from logline to BS2 to Board to script. We learn that in the workshops. Always a work in progress. In every step we learn something new about our heroes and stories. Yet those steps, including the beat sheet, lead to a story that resonates.

I think the point of the exercise is to talk about a film. What makes it work? What doesn’t? Blake’s genres and beats give us a language to enable our conversation.

To the detractor above: I agree with the two responses posted after you. A great term I learned a long time ago for the Beat Sheet is “Road Map”. Think about that: the road map tells you where you are going, but can’t possibly include all the details that will make the trip memorable. And I do agree particularly that it’s hard to retrofit a movie, especially a classic one, into a formal structural paradigm. But the point of this exercise is to show how all great movies are well-structured, and the Beat Sheet (or Road Map), is a great tool for helping writers achieve that structure. Peace out.

On a coffee break from one of his workshops Blake told me that he developed the BS2 and board technique so he wouldn’t get stuck on the process of scripting the screenplay. He could use this “road map” to get through to the end and get the story on the page (in first draft form). It is skeletal and as Jose says it is a tool to help move the writer forward. Nonetheless it is a good exercise to retrofit completed films into the beat sheet for no other reason than to familiarize oneself with the common story beats that good scripts possess. It should not be mistaken for a representation of the finished artistic product.

I agree with the above comments re: the Beat Sheet as road map, and I think what’s helpful about examining existing movies in terms of the 15 beats is that you start to get a feel for what kinds of things happen in each section of a movie, what kinds of scenes might work best where. (I hope that makes sense.) When you have a feel for the flow of a good story, it helps you organize your own scene ideas into a working roadmap to guide you in completing a first draft. Personally, I find the BS2 helpful as a brainstorming exercise and as an organization tool for all the little bits and pieces I come up with while the idea is unfolding in my brain. Just my two cents.

I obviously didn’t make myself clear. I’ll try again.

In many simpler screenplays, it’s true that the details, one-liners and character beats (meat) sit on top of a deeper structure (skeleton). However, many great screenplays, The Apartment included, are great because whenever you try and separate out skeleton from meat, you discover a complex web of interrelated parts. A “beat sheet” like the above needs to pay at least some attention to this additional layer of structure or what’s the point of it?

There is great value to be had in analysing a wonderful screenplay to see how the writers achieved the effects that they did – like taking a watch apart to see how it works. But reading the beat sheet above, it seems to me as if its authors have no idea how The Apartment works. To continue my analogy, it’s as if they’ve taken a watch apart and then simply listed the parts in order of size, giving no indication as to their function or interrelation.

If this is supposed to be a (retrofitted and therefore artificial, but still) road map for how to navigate your way through writing the movie, then it fails. Take the scene where “Baxter brings a random girl home drunk.” How do you write this scene without losing sympathy for Baxter? The structure-first-then-artistry approach is of little help. Sure you can have the random girl seduce Baxter rather than the other way around, and give her a husband so she seems more sinful than him, both of which help, but we may still feel that this is a bit tasteless. Wilder and Diamond solved this problem, but this beat sheet wouldn’t have helped, because the solution isn’t in this scene – it’s in earlier scenes.

Due to the constant traffic of executives clutching his key through the apartment, Baxter’s neighbour, the doctor, hearing constant “partying” through the walls has formed the impression that Baxter is some kind of Herculean lothario. When Baxter, seen (and half-admired) as a rampant ladies’ man is given the opportunity to live up to his reputation, the audience can hardly blame him for taking advantage. When he finally gets a girl of his own back to The Apartment, we kind of admire him too! There’s no way of knowing this from the beat sheet however, which almost entirely eliminates the character of the doctor. Just because he doesn’t have much screentime, doesn’t mean he isn’t crucial to the screenplay. I could give similar examples for almost every “beat”.

Most irritating of all is the pseudo-structural line “he is no longer alone in his apartment.” This seems to be a contrast with earlier images of Baxter alone in the apartment, but these are not only absent from the beat sheet (so again, the writer fleshing this out has no usable road map at all) but absent from the movie itself. There is no repeated image of Baxter alone in the apartment. In fact, the most striking image of loneliness is the repeated image of Baxter alone *outside* the apartment while executives play with floozies in his living room. There’s a difference between “beating out” a movie and rewriting it, surely!

So, I’m not opposed to the idea of creating beat sheets for famous movies, and I accept that this retrofitting is an artificial and so necessarily imperfect exercise. I just think it can be done well or badly. When it’s done well, the reader will gain a greater understanding of how the movie in question works. When it’s done poorly, such readers may be left with the sense that those writing the beat sheet don’t really know how this movie works. In my opinion, this beat sheet was done poorly. Which is a shame as The Apartment is a truly brilliant screenplay, structurewise.

THIS IS A LAZY BEAT SHEET. IT WAS A HEARTLESS EXERCISE AND THOUGH THE WRITERS OF IT MADE EXCUSES FOR THIS LAZINESS AND WERE DEFENDED FOR NO REASON. COME ON, NO SHIT A BEATSHEET IS A “ROADMAP” BUT WHEN YOU ONLY PAINT THE EXTERNAL MOMENTS AS BEATS YOU SHOW THAT YOU CLEARLY HAVENT REALLY DONE THE WORK. MAYBE YOU JUST DONT CARE OR SEE THE UNDERSTANDING OF BEATS AS A SURFACE THING BUT THEN YOUR NOT REALLY DOING THE WORK TO UNDERSTAND WHAT REALLY MOVES A SCRIPT. I HOPE YOU READ SOME OTHER INCARNATIONS OF WHATS MAKES A STORY OR OUTLINE ACTUALLY TICK. A GOOD BEATSHEET WHILE SIMPLE OUGHT TO HAVE EVIDENCE OF CHARACTER UNDERSTANDING AS WELL AS EXTERNAL PLOT MOMENTS. THIS APPROACH TO A BEATSHEET REALLY WOULDNT EVEN SERVE A GODZILLA MOVIE WITH ITS SHEER LACK OF DEPTH AND CARE. CAN YOU GET A DO OVER OF THIS AND “IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT”? YIPES. BY PEOPLE THAT ACTUALLY GIVE A RATS ASS AND ARENT JUST DOING “HOMEWORK”.